Mitch’s Blog

Travels with Harvey

Thursday, February 15, 2018

“Did I tell you about the 12 hour train ride I took with Harvey Oswald?” That’s usually a good conversation starter.

Bill and I drifted there from figuring out how to open the footlockers in his garage, the ones that held his most valuable books and his youthful writings, but for which he lost the key. The jingly ringful of hardware that we dragged out to the garage was no use. The footlockers married to those keys had long ago departed. But the one key we needed to confirm Bill’s diary entry of this encounter was sadly absent.

“Harvey Oswald? You mean Lee Harvey Oswald?” was my predictably incredulous answer.

“He called himself Harvey. October 15, 1959. I wrote about it in my diary at the time, but didn’t remember that we had met until sometime in the 1980s when I reread that part of the diary.”

I settled against a stack of boxes for the story. Bill Trousdale, once head of the archaeology project we are working on publishing together, was a young man on a journey of adventure that would take him throughout Asia for the next 18 months. He was an avid diary keeper—daybooks, he called them. This trip was no different. And, some day, the experiences of this pilgrimage would help him develop into a curator of Asian Art at the Freer Gallery. On this long-ago journey he also encountered Afghanistan for the first time, his passion for which would cause our lives to intersect 15 years later on his archaeological project and was the reason I was sitting on a box in a Pasadena garage and listening to an old man’s tall tale.

This tale begins on a train in Helsinki and ends in Leningrad, where Harvey travels on to Moscow and Bill stops to see the sights. The middle featured two younger Americans passing time during a twelve hour ride. A lot of time to talk, though Bill’s diary notes that his subject “didn’t have much to say.” Harvey has just been released from the US Army. Young, rebellious, confused, he was looking for advice on what to do next. Bill gave him suggestions and assured him that everything would work out. Harvey was up on politics, passionate about Russia, and knew things about world affairs that the studious Trousdale did not.

When they reached the Russian border, Bill’s luggage gets carefully combed over. Harvey’s does not. They take his books away. And his diary. The two tourists go to the restaurant at the train station. “It’s quite good,” Harvey assures him. The guard comes back with the diary.

“What is this?” A diary, a daybook, is the response. A blank look of incomprehension from the border patrol. A short time later, the book is returned to Bill. In the interim, Harvey asks what Bill writes in his diary and why. A flicker of interest passes through Harvey’s eyes. Bill never again sees or hears from Harvey after they part in Leningrad.

But the rest of the world does hear from Harvey in 1963. Bill, who did not own a television and knew the assassin by a different name, doesn’t make the links between his train companion and one of the most reviled murderers of the 20th century. Only in rereading his diary two decades later does he put together the pieces.

But the rest of the world does hear from Harvey in 1963. Bill, who did not own a television and knew the assassin by a different name, doesn’t make the links between his train companion and one of the most reviled murderers of the 20th century. Only in rereading his diary two decades later does he put together the pieces.

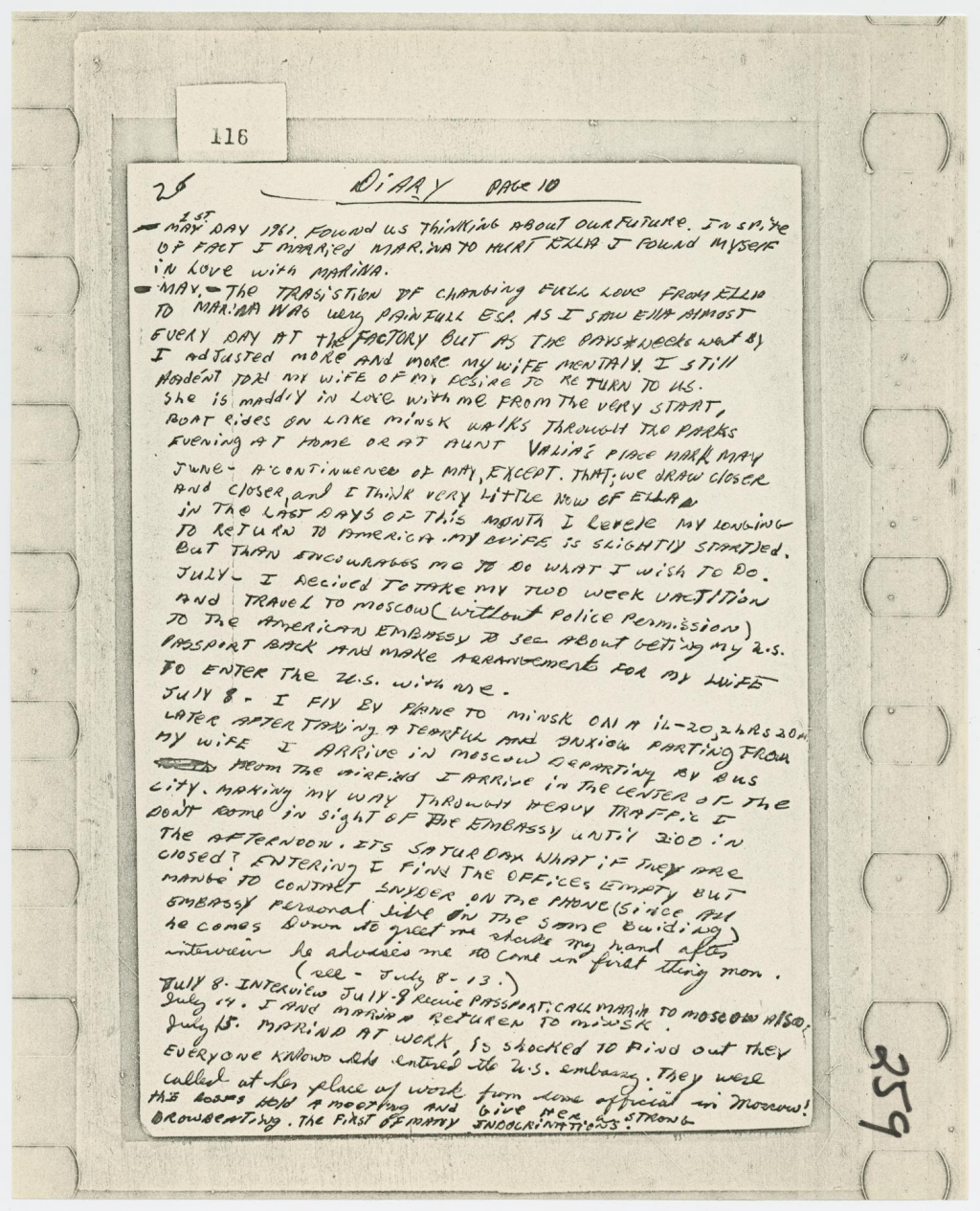

Oswald kept a diary too. It was purchased and published by Life Magazine, a year after the assassination. It begins

Arrive from Helsinki by train; am met by Intourist Representative and in car to Hotel "Berlin." Register as "student" 5 day Lux tourist ticket. Meet my Intourist guide Rima Sherikova. I explain to her I wish to apply for Russian citizenship. She is flabbergasted, but agrees to help. She checks with her boss, main office Intour, then helps me address a letter to Supreme Soviet asking for citizenship, meanwhile boss telephones passport & visa office and notifies them about me.

The date of Oswald’s initial diary entry, October 16, 1959, is the day after his train ride with Bill.

Bill’s account of this journey from the Finland Station is an old man’s tall tale, to be sure. But that evening Alexis and I went on line and confirmed most of the details in stories about Oswald’s travels. All that is left is to see Bill’s diary itself.

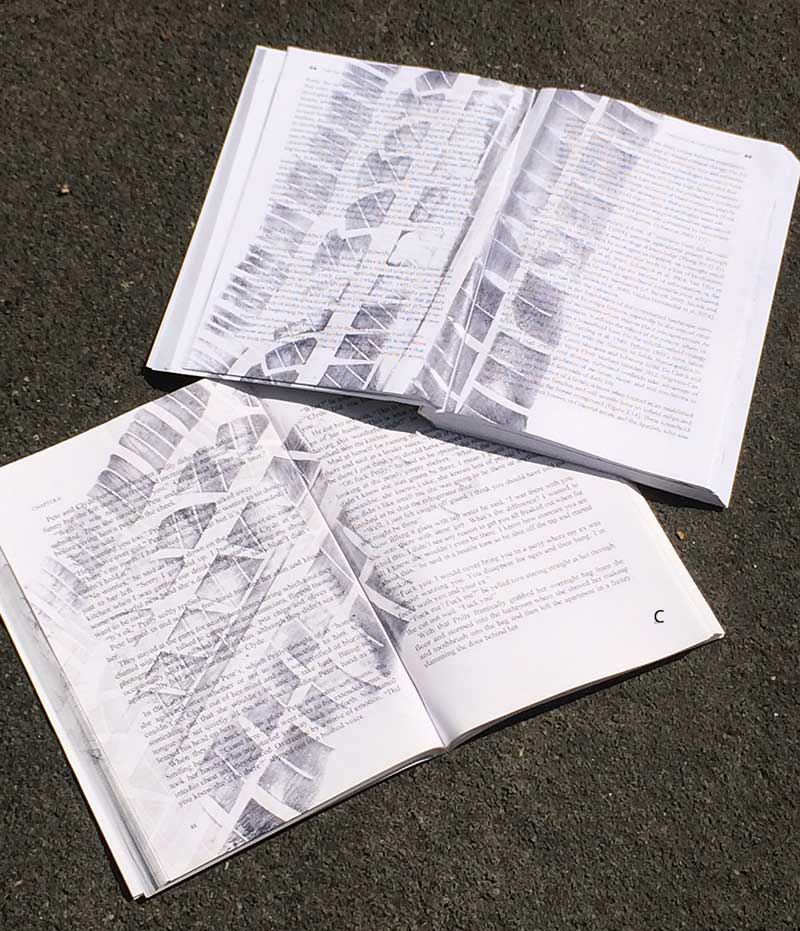

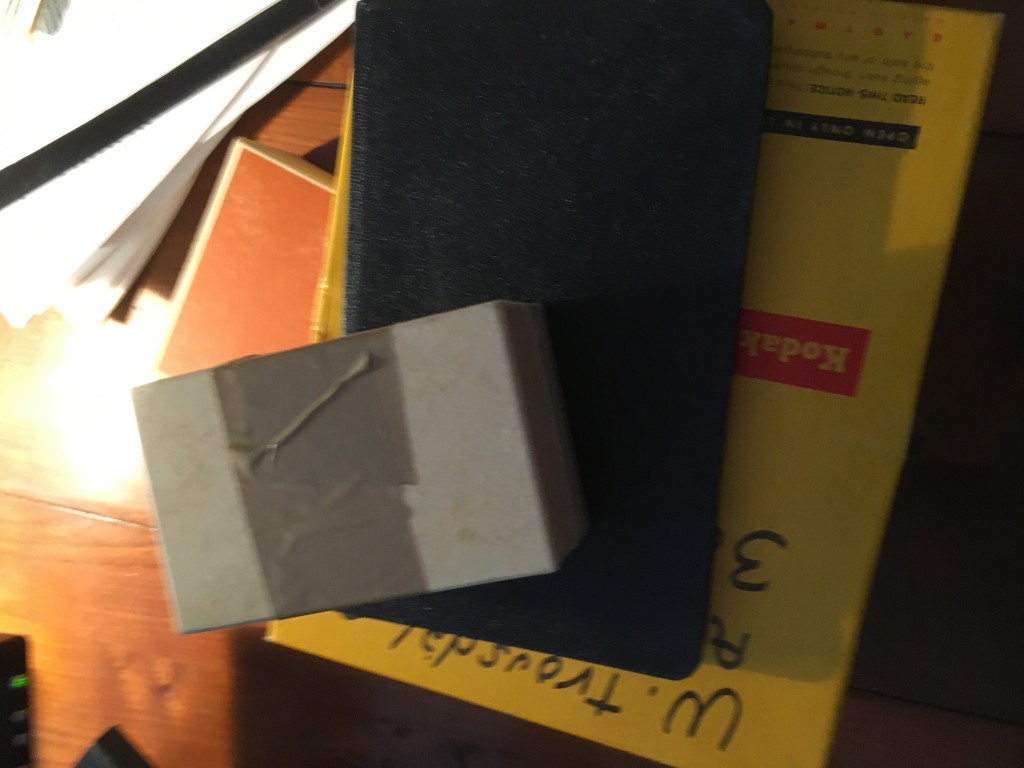

Roll the clock forward three months and I’m back in Bill’s garage, this time armed with a sturdy blue crowbar. “That trunk has all my diaries,” Bill point out the thick green chest from the three surrounding it. The imposing lock is gone in two flicks of my wrist. The trunk creaks when it opens. He’s curious to see the daybook himself. He’s told a skeptical neighbor the same story, now he has to produce the evidence. The row of brown leather volumes are carefully layered beneath a wad of large, pristine US government maps, each depicting a region of Afghanistan in the 1960s. I pull out a copy of the Lashkargah page to take home. We spent lots of time in Lash.

Roll the clock forward three months and I’m back in Bill’s garage, this time armed with a sturdy blue crowbar. “That trunk has all my diaries,” Bill point out the thick green chest from the three surrounding it. The imposing lock is gone in two flicks of my wrist. The trunk creaks when it opens. He’s curious to see the daybook himself. He’s told a skeptical neighbor the same story, now he has to produce the evidence. The row of brown leather volumes are carefully layered beneath a wad of large, pristine US government maps, each depicting a region of Afghanistan in the 1960s. I pull out a copy of the Lashkargah page to take home. We spent lots of time in Lash.

Bill carefully leafs through the volumes, the look of concern growing on his face. I pull out a couple of family photo albums from the side of the trunk that are impeding his search. “It’s not one of these. It’s smaller and with a mottled cover. You know what those writing books look like, don’t you?” It’s true, each of the identical brown leatherbound volume is carefully labeled, but the last one ends in September 1959, a month before the fateful journey. “I was sure it was in here. Maybe I took it out and brought it in the house.” He’s clearly puzzled, defeated, by the absence of the treasure we sought.

Nor was this the first time I’d gone treasure hunting—I’ll politely call it “doing archeology”— in Bill’s garage. It had already yielded 40 sand-covered field notebooks, 10,000 photos, and enough trays of slides to keep Cyndi busy for over a year scanning them all in, digitally documenting our field project in Sistan, Afghanistan 40 years ago.

With the targeted box empty, we moved on to the other trunks in hopes of finding it had simply been misfiled. No luck. There were, though, more missing Sistan photos and a copy of the slide that had been used as the postcard image of our project. Even better, a carousel projector box produced a small collection of labeled artifacts, objects that might have been left at the Kabul Museum in 1979 and destroyed during the Taliban era. Instead, they’re safely bundled in a Kodak box in Pasadena and will be repatriated after I’ve had a chance to study them.

And what of Bill’s story about Travels with Harvey? The evidence for it will have to await another day, another visit, another excavation season. Or I’ll have to trust him that it wasn’t just an old man’s tall tale.

(c) Scholarly Roadside Service

Lee Harvey Oswald photo courtesy of Warren Commission report

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life