Mitch’s Blog

Garage Archaeology in Pasadena

Friday, March 03, 2017

“Want me to grab you a couple of bottles of wine from the garage before I go?” I asked Bill. We had just finished three days of poring over draft descriptions of seventeen Parthian sites on the Malakhan Plain. I was ready to head back to Northern California.

“There’s lots!” I reply.

I knew this for a fact because I had been through his garage several times in the past year looking for field notebooks, photographs, slides, maps, plans, and photocopies of research articles with titles like “Notes on some volcanic and other rocks, which occur near the Baluchistan-Afghan frontier between Chaman and Persia,” published by the Royal Geographic Society of London in 1807.

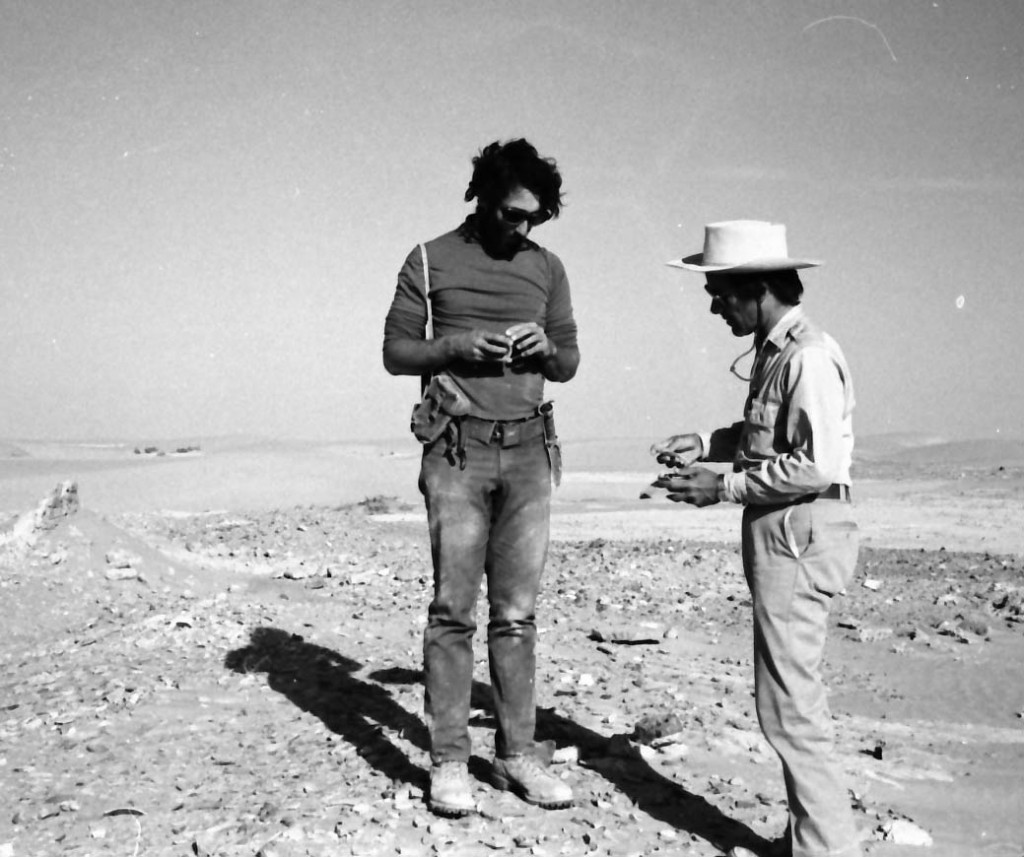

Archaeologist William Trousdale is just shy of 87 and a bit less mobile than I am when it comes to negotiating the treacherous corridors, precariously stacked boxes, and occasional scatter of rat poison in the loft of his Pasadena garage. Together, we are working on the field report for the Helmand Sistan Project, an archaeological survey of southwest Afghanistan that he headed as a Smithsonian curator and I participated in as a young Michigan graduate student in the 1970s. We spent many evenings in a tent surrounded by sand dunes hissing in the night wind, writing field notes to flickering Coleman lanterns. Now 40+ years later, we’re back at it to finish the field report.

The garage was its own archaeological excavation. Bill had shipped a wagon train of boxes from residences in France, England, and DC when he and Marion retired to Pasadena. Those boxes sat unmolested until I started ripping them open looking for material that we would need to write our report. Most of the boxes were filled with books from a lifetime of specialized collecting by two scholars: Afghanistan, colonial India, and Chinese art for Bill, English literature for Marion. No box weighed less than 40 pounds, and few were labeled so that I could safely leave its contents unexamined.

Calling it an excavation was no exaggeration. First there was the reconnaissance: ripping the tape on boxes with the label “Afgh” scribbled on them. Most had books published in Kandahar or Delhi, recounting the exploits of British colonels or Mughal emperors. Then we got more systematic. Boxes with “United” or “Pink” designations were from his Washington office and could contain the treasures we sought. Those were extricated and opened. The boxes that once contained Chiquita bananas or Scott Tissues we thought we could safely skip. Still, we managed to recover only a fraction of the corpus. Finally, we conducted a full stratigraphic dig. Layer by layer of boxes were systematically opened, examined, catalogued. Most were repacked and shoved back into dark corners of the garage. Those that contained items valuable to our report were carefully removed for further analysis.

There were some surprises. One box contained a hoard of old t-shirts, another a 3 year supply of skateboard magazines from the 1990s, still another preserved concrete bricks and fertilizer from a Maryland garden, packed by some unthinking (or was it sadistic?) mover. Still, as every popular archaeology book breathlessly recounts, the garage revealed its secrets. We found all the field notebooks, now digitized for safe storage in the global cloud. The boxes containing 5 x 8” photographic prints were tougher. Each garage field season uncovered more of them until we had amassed most of the 10,000 known photos in some fashion. When my aging body couldn’t twist itself into the cramped storage compartment under the garage stairs, we enlisted my stronger and more nimble son Josh to shove boxes around and find the right ones. Disappointingly, most contained books of Scythian art published in Leningrad half a century ago or catalogs of Chinese jades in German museums.

After a year of seeking and scanning, we had all the feral field notebooks captured and almost all the black and white photographic prints herded and confined on my hard drive. The crucial architectural drawings were located in a back office of the Smithsonian, where they have resided since Bill retired 20 years ago. They were never forwarded, nor could they be sent until that museum wing remodel was completed and the curators allowed back into their offices. Two centuries of published research articles on Afghanistan were left dormant in their boxes until we reached the comparative analysis phase in the project. There will be more garage archaeology in my future.

We were still short a coup le of boxes of photos and worried at how to find those missing rolls. Then, in my October visit, Bill emerged from his office with a large notebook containing negatives of every shot from the entire duration of the survey, long lost in the corner of a closet. The collection of field photos was finally complete.

le of boxes of photos and worried at how to find those missing rolls. Then, in my October visit, Bill emerged from his office with a large notebook containing negatives of every shot from the entire duration of the survey, long lost in the corner of a closet. The collection of field photos was finally complete.

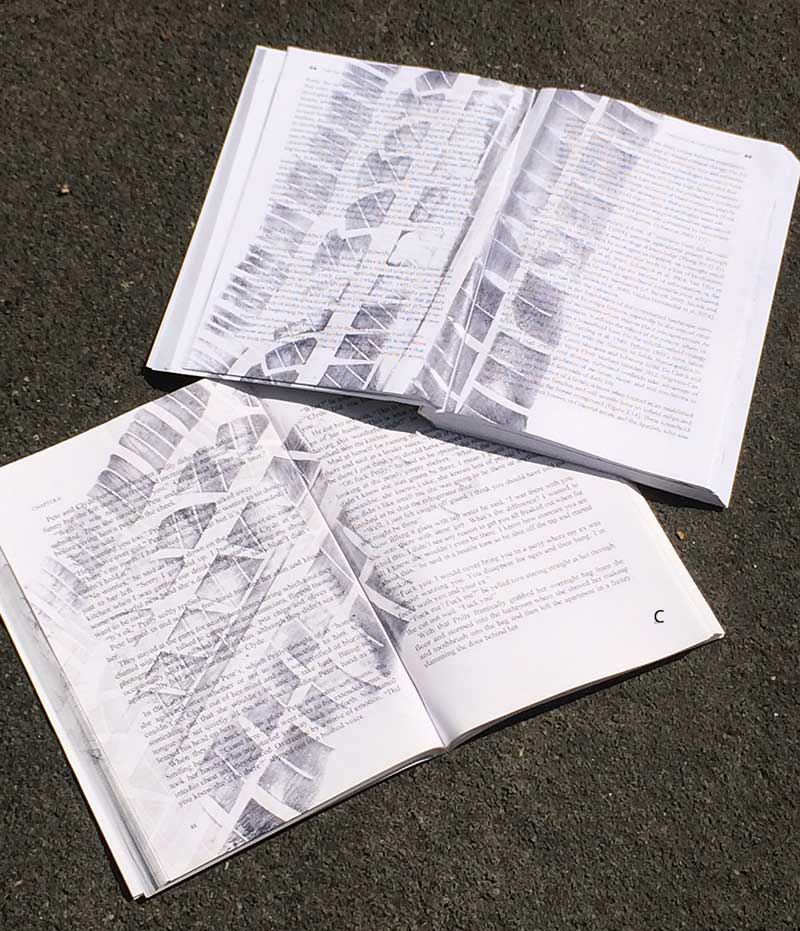

But what about the color slides? We knew from the photo logbooks that there were plastic boxes of slides from each of the seven field seasons, but we had only unearthed a single one from 1974 and another from 1977. In this social media universe of vivid color, how could we properly highlight our project with only black and white prints to display our work. True, most of Sistan was dull tan and gray desert, but Chip Vincent had taken slides of vivid purple sunsets over half-melted mudbrick towers framed by shadowy sand dunes, riotous blue, green, and yellow swirls of Islamic glazed pottery, and shimmering greens, silvers, and golds of coins picked up from their resting place of a thousand years.

As I slipped back into the gauntlet of Bill’s garage loft, I grabbed a white-labeled rioja and a couple of Italian bottles with mouse-nibbles erasing the fine print on the labels. Turning in the tight space I glanced up at a box above my head. A marker inscription on one side announced SLIDES. We had been through that part of the garage many times, but somehow that label had never raised its voice before. A careful twist-and-step motion avoided upsetting a dusty dozen wine bottles and brought the box off the shelf and down to eye level. Sure enough, labels on the plastic boxes inside listed 1971, 1972, and on and on. We have found the slides! Sistan will be in color.

© Scholarly Roadside Service

Afghanistan photos courtesy of Helmand Sistan Project.

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life