Mitch’s Blog

Truth is in the Basement

Thursday, May 07, 2020

Why a second glance? Because Dino, with his South Boston r’s bouncing off his tongue, has the food truck parked just outside the entrance to the Peabody Museum at Harvard University. Walk up the half dozen steps and you’re in one of the richest anthropology collections in the world babysat by some of its best known scholars. Plains Indian hide paintings in the first gallery, Maya sculpture upstairs. Round the back of the building a stele from Copan graces the lawn.

My route took me downstairs instead. “They always put us archivists in the basement,” my host said wistfully. True, archivists, collections managers, conservators, are always relegated to the basement. Dino may have to stand outside in the freezing New England cold for hours, but on a lambent spring day, he gets to take in the breeze, the dancing blossoms on the trees, the paintbrushed green of fresh lawns. The archivists? It’s the same 4 windowless walls, the musky smell of pipe tobacco, sometimes worse, emanating from some long-forgotten professor’s file boxes. Ask any archivist. That tobacco smell has a half-life longer than Carbon 14.

I was there a year ago to look at the files of Walter Fairservis, an archaeologist who had worked in Sistan, my part of Afghanistan, around 1950, when it was even wilder territory than when I passed through. I never had a chance to meet Fairservis, who died in 1994, but wish I had. In addition to his archaeological work, he also wrote and produced stage plays, was curator at the American Museum of Natural History in NY, and served on General MacArthur’s staff during World War II.

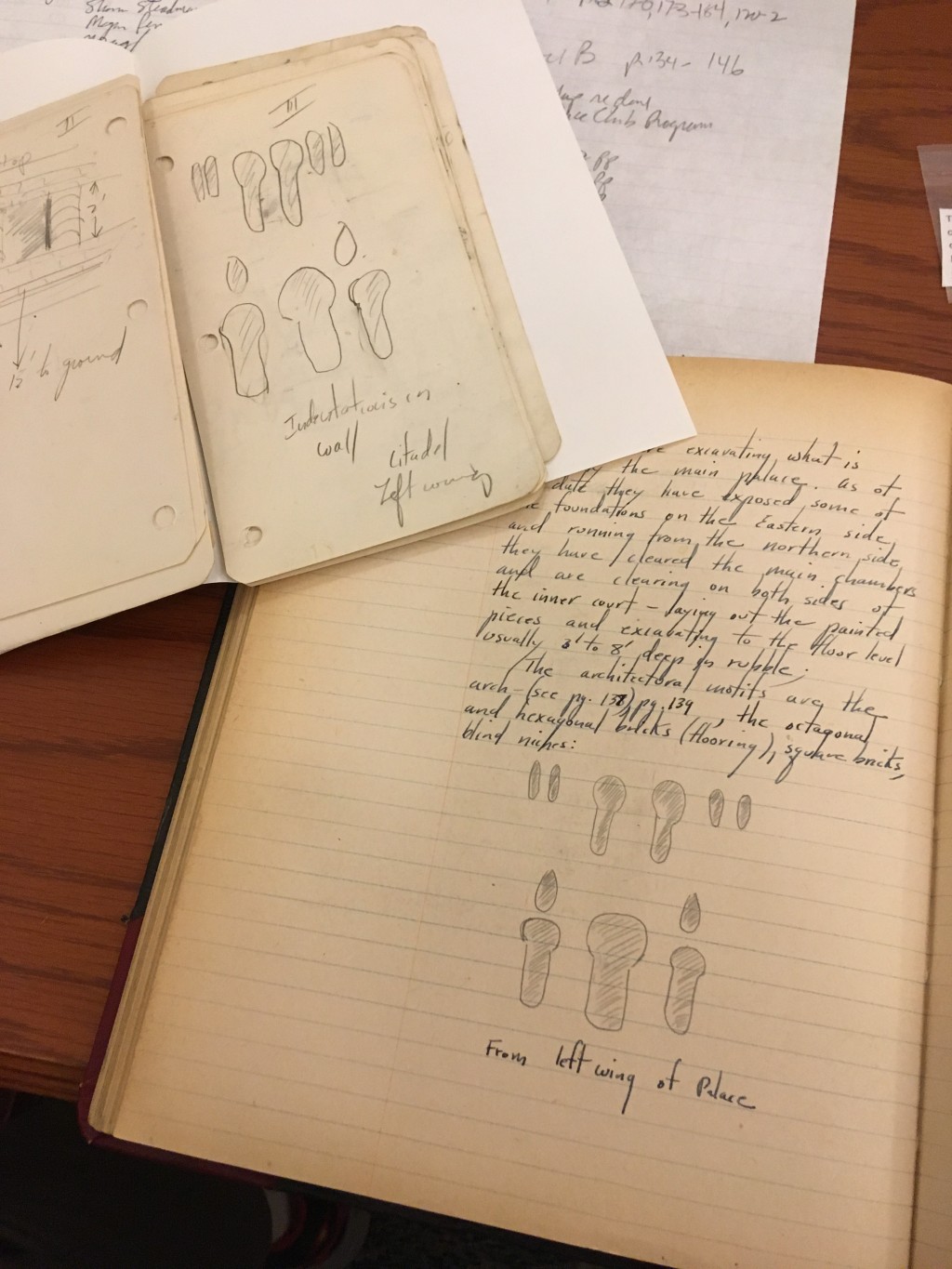

Fairservis’s notebooks on his fieldwork in Sistan contained invaluable information. Descriptions of sites I will never see, thoughts on the geology of the region, descriptions of contemporary villages that match the book on this that I am currently editing. And there were other bits that were far more interesting.

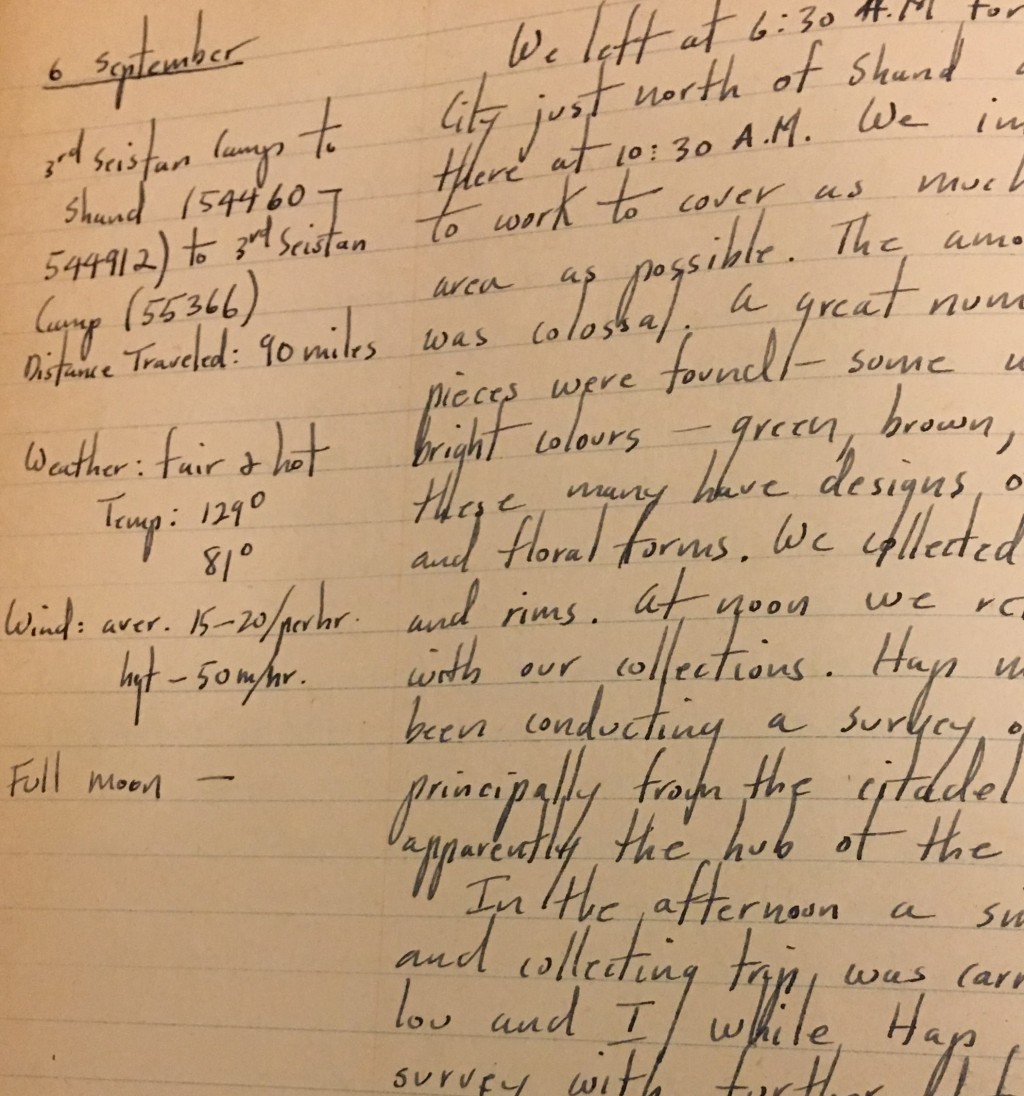

I’ve read from the 19th century British visitors to Sistan about the Wind of 120 Days, the summer stretch when the temperature skyrockets and the winds howl for four full months. We didn’t do our field research in summer because of this. Fairservis ignored the warnings and conducted his first survey season August and early September. His daily entries always recorded the temperature and other weather information. September 6 showed a high of 129 degrees with 50 mph wind gusts. Besides being a miserable day to be an archaeologist, it certainly raises questions of how good research was that day.Unlikely he could see much of anything through the blowing sand and dust. And, if he and his team were human, they didn’t spend very much time at the sites they visited that day. None of those caveats made it into his final report of the survey.

Fairservis ignored the warnings and conducted his first survey season August and early September. His daily entries always recorded the temperature and other weather information. September 6 showed a high of 129 degrees with 50 mph wind gusts. Besides being a miserable day to be an archaeologist, it certainly raises questions of how good research was that day.Unlikely he could see much of anything through the blowing sand and dust. And, if he and his team were human, they didn’t spend very much time at the sites they visited that day. None of those caveats made it into his final report of the survey.

Equally puzzling was the quality of his field notebooks. I too worked in Sistan and, even without howling winds and blistering heat, I wouldn’t be writing my notes in ink in complete sentences carefully placed upon the page. I was amazed at his ability to do. Where are the coffee stains? The grains of sand caught between the pages causing his pen to slip?

It was only then that I found the real field notebooks, scribbles on scraps of paper and small portable binders that had all the original notes. In pencil. With coffee stains. The beautiful, leather bound “field” notebooks were for posterity. A nice gesture to people who came after, like me, but it wasn’t his raw observations on the ground. Ironically, I may be the first person who has read these prettified notebooks since he wrote them in 1949.

Archaeologists come by our reputation as academic cowboys honestly. We’re always crass in the field. One site we visited that spanned two mounds was labeled Two Tit Qala. An ancient structure pouring sand out its doorway was labeled the Barf Building. None of this makes it into our final publication report. They will be “Qala 212” and “Public Building 14” respectively. So I was thrilled to see the the field notebook mention a site called Fairservis’s Pimple. That name didn’t end up in his final report either.

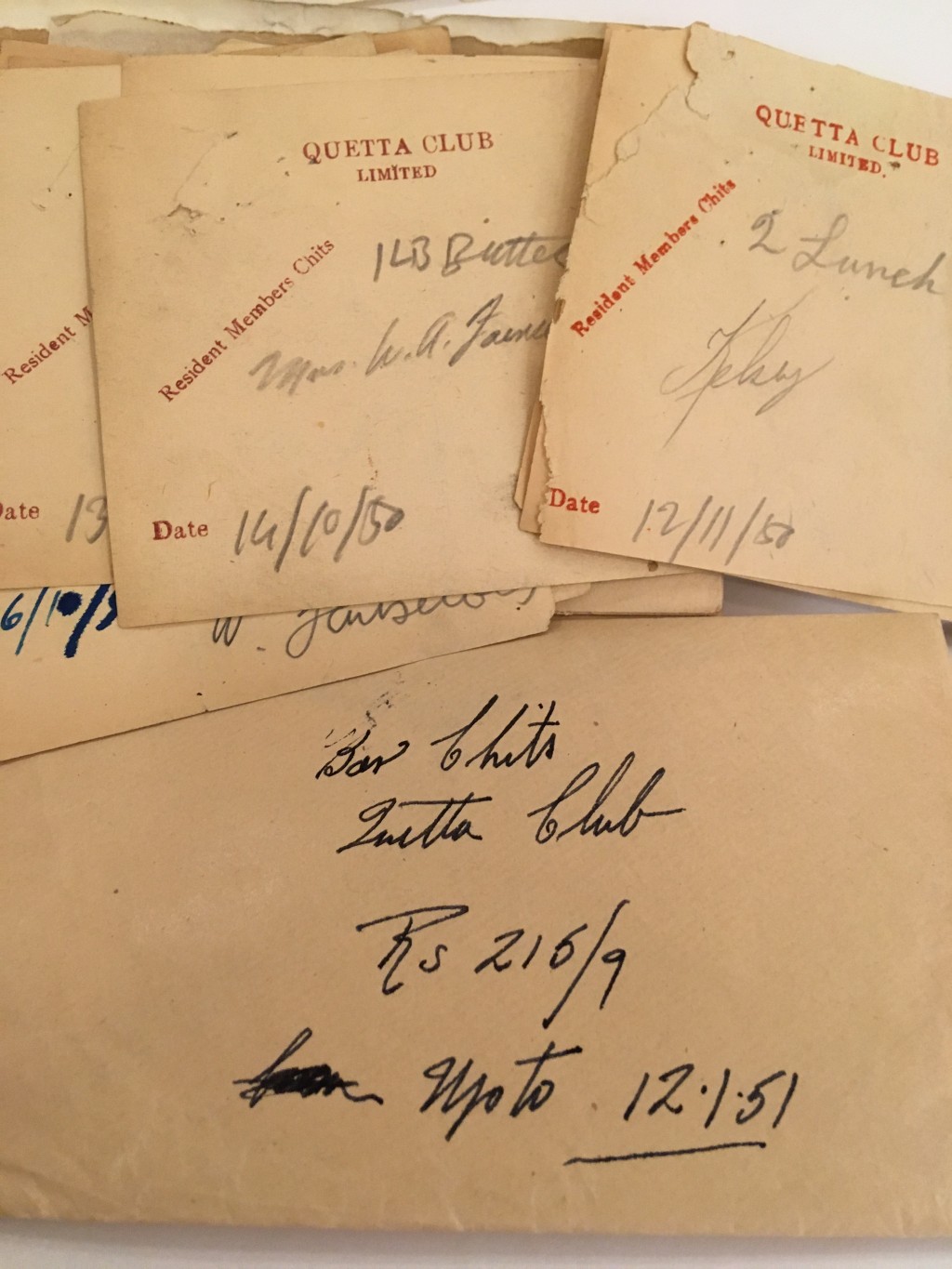

That report, published in 1961, also ignored tales of the field that weave throughout the notebooks. The day they ran out of gas in the desert and a staff member had to walk 15 miles to the district capital to beg for petrol, which was brought to them on the back of a camel. The details of being sick in the field. TMI. The letter from the Pakistani Antiquities Department inquiring about a shipment going to New York that was recorded by Fairservis as “personal effects” but contained bags of ancient ceramics from his field sites. Fairservis didn’t end up spending his last years in a Peshawar jail, so I guess that problem was resolved. Chits

The dirt on his later-to-become-famous colleagues certainly enlivened my days in the basement. About one: “If he sticks to the facts of his work rather than anything else, he’ll make a good report.” Another “has so far failed to produce a substantial monograph representing a study in depth.” And, of course, the French archaeologists who dominated work in Afghanistan for 4 decades: “we know so little of Buddhist pottery. This wouldn’t have been so if the French had been a little more conscious of their obligation to archaeology and less to art.” Walter was also asked to evaluate our Afghan project proposal for NSF. I found the request but not his response. Must have been favorable since the project was funded for almost a decade.

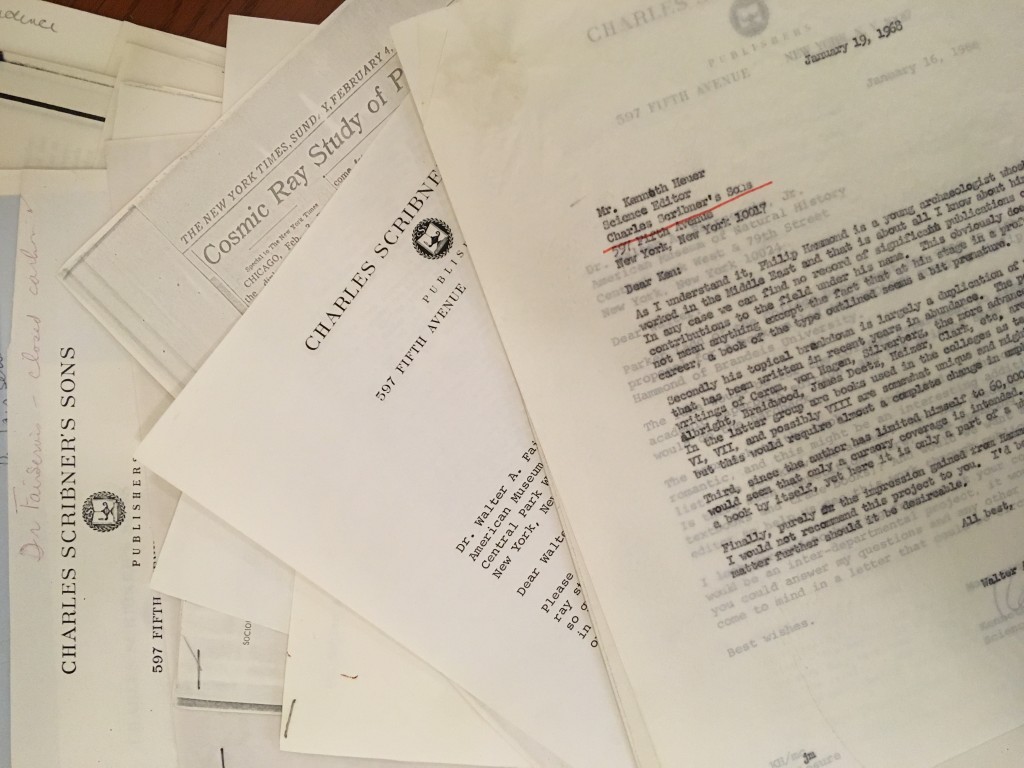

Fairservis was a highly published archaeological author and editor in the 1950s and 1960s, so I delved into some of his correspondence with publishers as well. His contract for a series of sciences books with Scribner was cancelled by Charles Scribner Jr himself.

Reading this archival material has put flesh on the dog-eared field reports sitting on my shelf. I liked the guy whose notes I read and wish we had shared a drink at an archaeological conference sometime. And it’s given me added incentive to finish my own research project in collecting the millions of bits of flotsam from the Helmand Sistan Project, publishing the findings, and placing all the rest into an archive at the Smithsonian. Some future archaeologist will hopefully peruse it some day in another 50 years and wonder about the bunch of us who spent those months in the Sistan desert.

© Scholarly Roadside Service

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life