Mitch’s Blog

The Thanksgiving That Almost Wasn’t

Monday, November 27, 2017

My favorit e Thanksgiving dinner was one I almost missed. I won’t post a picture of the feast on Facebook. Not only had FB not been invented, Mark Zuckerberg hadn’t been either. It was November 1974 and I was in Afghanistan.

e Thanksgiving dinner was one I almost missed. I won’t post a picture of the feast on Facebook. Not only had FB not been invented, Mark Zuckerberg hadn’t been either. It was November 1974 and I was in Afghanistan.

It’s fun to reminisce about past holiday meals when you’re stuffed with leftovers, watching the Tupperwares of turkey and dressing rapidly disappear from the refrigerator as the whole family regularly dips in. Thanksgiving in our camp on the Sar-o Tar plain was a bit different. Centerpiece was the turkey of course, straight out of half a dozen Swanson cans and decoratively arrayed on plastic serving vessel by Barat, our Hazar cook. Knowing it was a special night, Barat went all out. While I don’t exactly remember the menu, I’m sure he pulled open cans of cranberry sauce, jars of string beans, and probably boiled a pot of rice as secondary dishes.

This doesn’t sound like much of a feast, I know. But we had been living in the field for three months and subsisting on Spam, Chef Boyardee, Skippy, various canned fruits and vegetables, and lots of rice. The only food I never skipped was the fresh nan that came straight to the table from the tandur built by Barat’s assistant. And, of course, the liquid refreshments. We brought plenty of alcohol into the field with us. As the night closed in, leaving only flickering light of Coleman lanterns in the work tent and surrounded by howling wind, hissing sand, and dropping temperatures in the late autumn desert, a glass of sherry or scotch seemed a good companion to writing fieldnotes before making the dash to my sleeping tent through the biting wind.

As the night closed in, leaving only flickering light of Coleman lanterns in the work tent and surrounded by howling wind, hissing sand, and dropping temperatures in the late autumn desert, a glass of sherry or scotch seemed a good companion to writing fieldnotes before making the dash to my sleeping tent through the biting wind.

Thanksgiving dinner was something to look forward to and was regularly discussed as we reveled in our food fantasies while dining on Barat’s canned repasts. We had planned for the holiday, buying cans of turkey at the US commissary before launching into the field. Had Barat forgotten an ingredient or two, it would have been hard to replace. The commissary was 400 miles away in Kabul. Desert Afghanistan had no 7-11s either.

We were transient that week, like the camel caravans we regularly passed. We had spent two months excavating sites near the massive abandoned city of Shahr-I Gholghola, the City of Screams, embedded in the dunes of the Sar-o Tar plain. To finish the season, we moved northward on the dasht, the plain, to find and document many of the other structures we could see from the city’s citadel. We’d camp for a couple of days next to one 11th century ruin, plot sites sticking out of the dunes within a day’s walking distance, then pack up and move a few miles further.

Not everything we recorded was in the sand dune field. We often took jeeps across the unsanded portion of the dasht to visit fortresses, houses, and masoleums we could see in the distance. Late the afternoon of Thanksgiving, I bolted from my tent, grabbed the keys to one of our Land Rovers, and sped out of the dune field to inspect a site I had seen earlier that day.

Not everything we recorded was in the sand dune field. We often took jeeps across the unsanded portion of the dasht to visit fortresses, houses, and masoleums we could see in the distance. Late the afternoon of Thanksgiving, I bolted from my tent, grabbed the keys to one of our Land Rovers, and sped out of the dune field to inspect a site I had seen earlier that day.

It was majestic. Squared walls of a medieval mudbrick fortress towered far above my eye level. An S-shaped entry, massive round corner towers, and square ones along each wall. Melted piles of mud hinted at buildings that once stood inside the walls. Glazed ceramics of brown and green littered the ground, sure indicators of the 11th century. My collection bag of pottery was soon full as I walked around the fortress drawing a quick sketch plan. The rapid descent of the desert sun and of the afternoon temperature were signals to end the day’s exploration. I jumped into the jeep headed for camp and turkey dinner.

Those familiar with National Geographic photos of a sea of Saharan sand wouldn’t recognize the dunes of Sistan. Rather than a sea, they were lapping waves, some dunes the size of three story buildings, others small enough to play leap frog. Each crescent-shaped dune followed its own path and pace across the dasht leaving unsanded areas between. And, like any traffic pattern, a certain level of congestion is expected. Dunes bumped up against each other, absorbed each other, or crossed each other’s path. Whenever the dunes intersected, a wall of sand cut off the path for my jeep. In short, negotiating the dune field back to camp was like wandering through a rat’s maze toward the reward at the end.

I was sure of the route, and there was still a bit of fading light to help me. Enter the dune field at the remains of some abandoned field walls, A couple of bumps over 15th century canals, a sharp turn before the mountainous dune swallowing a Sassanian house, two more twists and I’m there.

I missed a turn somewhere.

Dead ended at a pair of crossed dunes, I retraced my steps and tried again. And again. Then tried a different path. Then another. All the while, white sun turned to pink sunset turned to black of evening. I was lost.

It must have been half an hour of driving in circles past the same set of dunes before I gave up. I knew that the camp was close—we weren’t far into the dune field—but knew also that I wasn’t going to find the route home. A quick inventory: I had my down vest and a grungy sleeping back in the back of the jeep. Half a canteen of water. No food. I’d curl up in the cold as best I could, sleep in the jeep, and look for my companions again in the morning. But miss turkey dinner. If sitting in the work tent under faint light with cold, windy darkness all around was eerie, sleeping in a jeep by yourself in a vast sandy desert was a dimension scarier.

That’s when I heard the engine. I was unable to determine its direction, but knew it was close. A few minutes later, our project driver Niaz Mohammed rounded the corner of my dune in another vehicle and motioned me to follow him back to camp. He and the rest of the team had climbed atop a highest dune above camp and watched me driving in circles a few hundred yards away. “Wasting gas,” was Bill the project director's only comment. Refilling the gas tank was far more complicated than driving to the local Mobil station. After a straw vote, Niaz had been sent out to rescue me.

I was the butt of endless jokes that evening. But turkey never tasted so sweet, even if it came out of a can.

(c) Scholarly Roadside Service

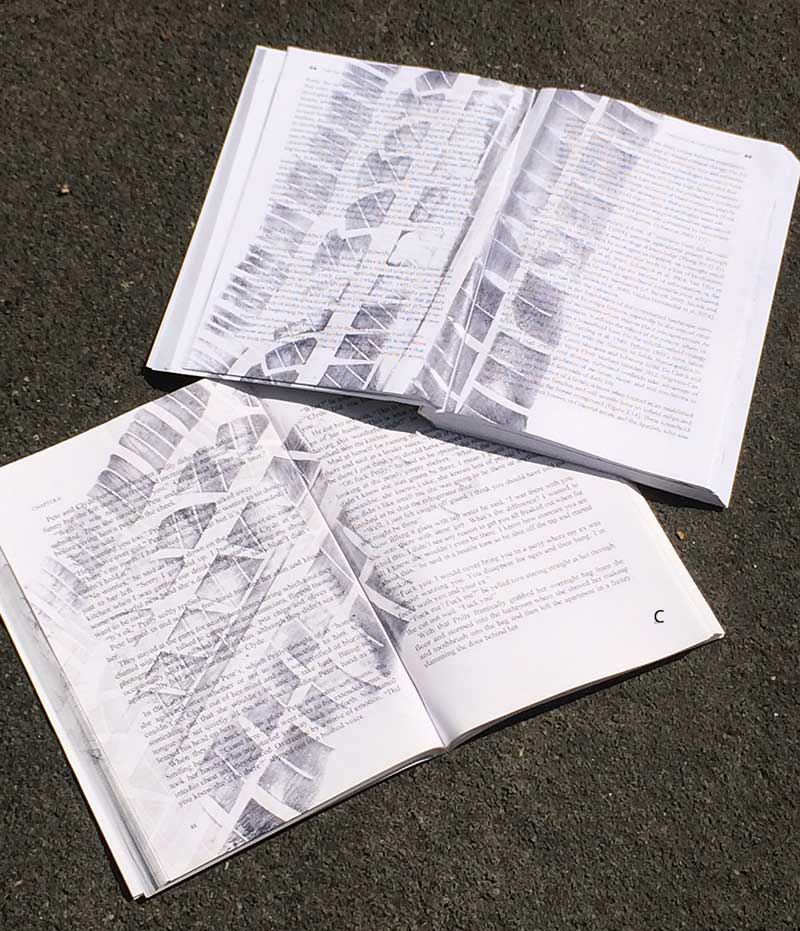

Photos by Robert K. Vincent, Jr, courtesy of Helmand-Sistan Project

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life