Mitch’s Blog

The Non-Mysterious Past of Publishing

Friday, November 24, 2017

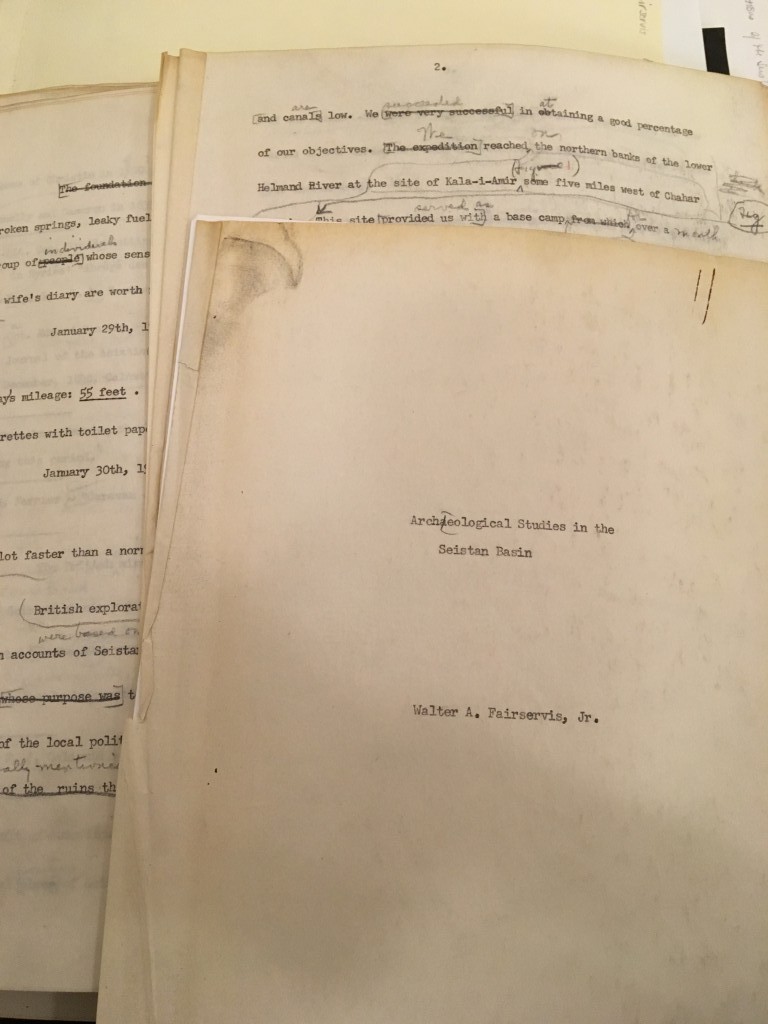

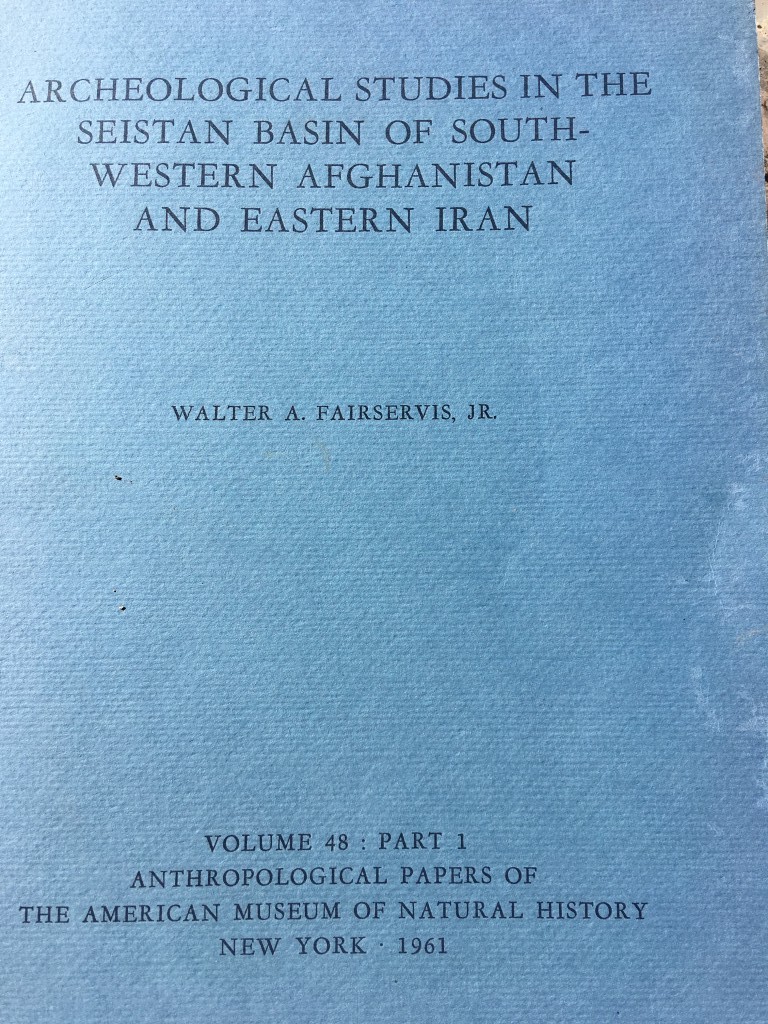

I was there for a very different reason. Fairservis had explored the Helmand River Valley in Afghanistan the year I was born and recorded dozens of archaeological sites. His published report, creatively titled Archaeological Studies in the Seistan Basin of Southwestern Afghanistan and Eastern Iran, Volume 48 Part I of the Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, contained much of the information I needed for my research on this region based on the archaeological project that I participated in during the 1970s. But what didn’t he include in that detergent blue-covered survey report? A couple of days with the Fairservis papers at the Peabody archive was the ticket to find out what else he could tell me about Sistan.

The simple answer was that not much had changed. I saw in this correspondence the same phrases that I kept in my shoebox of excuses of why we wouldn’t publish someone’s book:

- “based upon our marketing department’s assessment of potential sales, we will have to forego the pleasure of publishing your exemplary research”

- “while the project is of great interest, our list in this field has developed in a different direction”

- “the peer reviews we received were not strong enough to warrant moving forward” and, of course, the ultimate passive-aggressive response,

- “we don’t feel we can do justice to this excellent work”

Many of these phrases, as all editors know, are encoded ways of saying: “This is a stupid idea,” or “when will you ever learn to write,” or “I hope you have a lot of relatives because no one else will buy this book,” or “this might be a great book, but you’ve been such an asshole in this dialogue that I wouldn’t publish your book under any circumstances.” Though the editors’ names have changed from the Scribner crowd, the language of editors has not.

There were a couple of differences, though. The manuscript of

Even more eye opening were the illustrations for Fairservis’s proposed coffee table book for Thames & Hudson. Lost Civilizations. An artist was commissioned to paint the illustrations for the book based upon notes from Fairservis and his editor. To paint them. And there, in the files, were the first drafts of the paintings. Each contained notes of changes required for Miss Chapman, artist, for when she would go back to the literal drawing board and paint the picture over again. A far cry from scouring Wikimedia or one of the stock photography companies to pull a few images for a book.

As an archaeologist, there is always the temptation to imagine myself back in the time periods that I am studying. But having myself bridged the analog to digital decades in publishing, it required very little imagination to eavesdrop on a 1962 editorial meeting in Scribner’s Fifth Avenue office. I’ve lived this meeting and dozens of others like it. I’ve written the resulting letter to the author in almost the same words.

This is one case where The Mysterious Past really holds no mystery.

(C) Scholarly Roadside Service

Thanks to the Peabody Museum Archive in Cambridge, MA, for allowing me to browse their files on Walter Fairservis

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life