Mitch’s Blog

“So How Was Cuba?”

Monday, May 14, 2018

“Did you have a good time?” A reasonable question to someone who has just returned from such an exotic place. But I wasn’t ready for it the first time. The guys had just come back from their dawn run and were sipping water on Tony’s porch. I’d returned the night before and was simultaneously sleepwalking and walking the dog. “So how was Cuba?” one piped up.

How to craft an answer? Was it the invigorating music and dance we saw everywhere? That’s what Becky and her crowd would want to know. Or the visible differences between their socialist system and our capitalist one? Nicole and Peter asked me about that later in the day. The antique cars? Neil would be all over that. The oppression by a dictatorial regime? The difference from the United States is shrinking by the day. Cuban food? Lots of listeners would want to start there. Cigars? Rum? The May Day celebration we were able to witness? None of those matched my own impressions of Cuba.

I could have started with our tour guide, born after the revolution and raised in its worldview, which he expressed to us regularly, a storyline different from the one we’ve heard all our lives. The Bay of Pigs Museum, which gloated over their country-saving victory, much as we celebrate Yorktown or Gettysburg or Midway. The experience of the lush green of a boundaried tropical island from someone who lives in endless semi-desert California.

Our guide Jean’s perspective on Cuban/American differences were revelatory. He pointed out the fact that there are no homeless in Cuba, no unemployed, that everyone has access to free medical care, that the mentally ill are not pushed onto the streets. Then he proceeded to describe the era after the fall of the Soviet Union and cutoff of their billions of aid to Cuba; where no one had enough to eat or enough of a pension to buy even the basics. “We lived on a piece of bread and a cup of sugar water every day.” He blames the US embargo, now going on 60 years. He’s probably right.

In the US, we were told the Mariel “boatlift” of 1980, in which over 100,000 Cubans sailed from Mariel to Florida, consisted largely of Cuban undesirables—criminals, menta

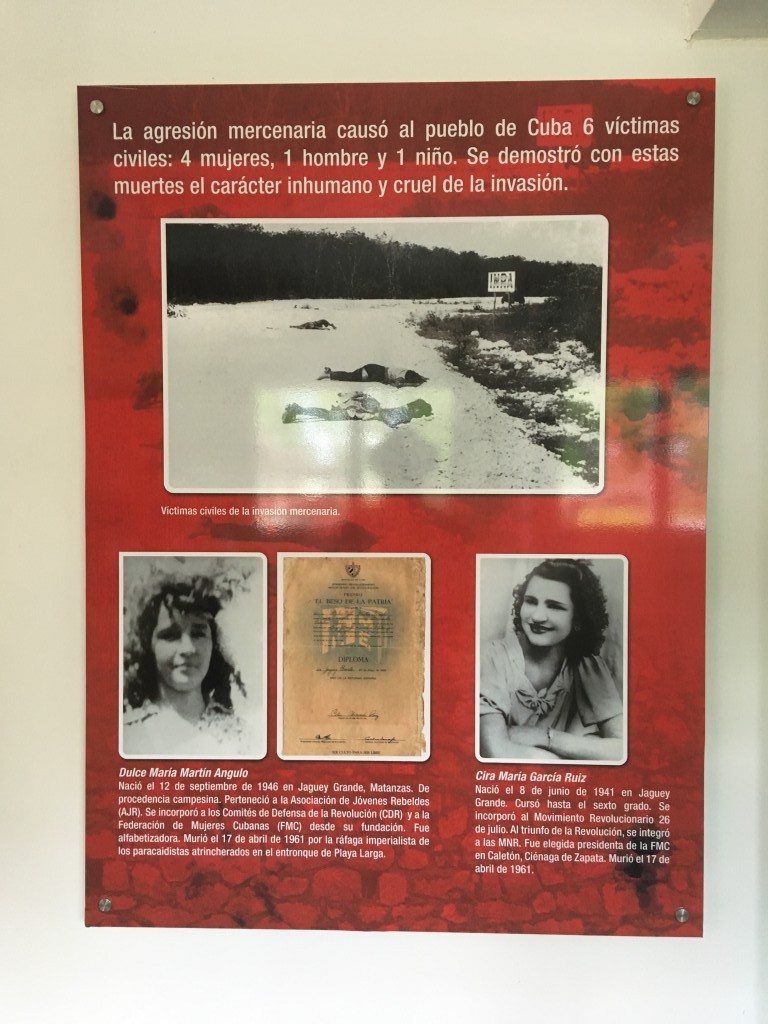

Anyone who has been to a pre-Vietnam American war memorial is given the storyline of the brave Americans and how their actions helped preserve the republic. The Bay of Pigs museum at Playa Girón is no exception, except for a reversal of roles of the good guys and the bad guys. There is a wall to the Cuban martyrs ruthlessly killed by the US-backed mercenaries who invaded the sacred soil of southern Cuba. Photos of the napalm attacks by the mercenary air force, raising the question of why the US military would hand over such nasty stuff to them. A panel with biographies and photos of the half dozen civilians cut down in cold blood by the invaders.

Havana, once the playground of the American and Cuban rich, now is filled with the hollowed-out structures of their excesses. Imposing columned porches, intricately designed architectural elements, colorfully painted walls all collapsing and peeling and molding after half a century of disuse. The archaeological trope of “squatter occupation” after the destruction of a site took on a more concrete meaning when we could observe how these crumbling places are occupied by poor Cuban families. The few reconstructed buildings in Habana Vieja were breathtaking, but with limited funds available most of the 1950s structures are becoming archaeological.

Not so the 1950s automobiles, which have become one of the most visible tourist attractions of the country. Taxis rides in a 1949 Plymouth convertible are the equivalent of rickshaw rides in Beijing. Packs of cherry red-pink-blue-purple classic cars line the streets in central Havana and most other tourist locations. Equally promoted to tourists are the visage of Che Guevara and Ernest Hemingway.

Not so the 1950s automobiles, which have become one of the most visible tourist attractions of the country. Taxis rides in a 1949 Plymouth convertible are the equivalent of rickshaw rides in Beijing. Packs of cherry red-pink-blue-purple classic cars line the streets in central Havana and most other tourist locations. Equally promoted to tourists are the visage of Che Guevara and Ernest Hemingway.  Che adorned buildings all over the country as well as any tourist item you could buy in the government controlled souvenir markets. Hemingway’s bulky shadow hovered over at least two homes and three bars that we visited. Jean’s description of him as a humanitarian, environmental warrior, and true friend of the Cuban people didn’t match my understanding of him as a self-centered, misogynist, animal-slaughtering asshole. I don’t like his books much either.

Che adorned buildings all over the country as well as any tourist item you could buy in the government controlled souvenir markets. Hemingway’s bulky shadow hovered over at least two homes and three bars that we visited. Jean’s description of him as a humanitarian, environmental warrior, and true friend of the Cuban people didn’t match my understanding of him as a self-centered, misogynist, animal-slaughtering asshole. I don’t like his books much either.

But the strongest impression was that we never saw Cuba. Shepherded by our tour guide, we were housed in beach resorts far from the center of town each night. We were entertained by musicians and dancers at each meal and fed a rich diet of pork, chicken, beans, rice, mangos, and vegetables. Fruity drinks with lots of rum were ubiquitous. We drove past boxy Soviet-style apartment buildings, quiet farm towns with people sitting on their stoops, squalid downtown Havana neighborhoods, busy industrial zones, and bustling commercial districts. But our itinerary didn’t include any of those.

“So how was Cuba?” I’m not sure I can tell you.

© Scholarly Roadside Service

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life