Mitch’s Blog

The Book That Took 50 Years to Publish

Thursday, November 03, 2022

Bill outlined his vision for our book almost half a century ago as we sat at the foldup dinner table in a domed room of the compound of Hajji Nafaz Khan, ruler of the village Khwaja ‘Ali Sehyaka and our gracious host.  Pigeons filled the crevices of the crumbling mudbrick building by night; bats occupied those same spots during the day. The shift changed at dusk with a cacophony of squeaks and caws amid hundreds of flapping wings. The desert nights had us tightly bundled up. Jackets would be shed the following morning as we trudged a few yards up the hill to excavate the Hellenistic temple at Sehyak in the blazing autumn desert heat.

Pigeons filled the crevices of the crumbling mudbrick building by night; bats occupied those same spots during the day. The shift changed at dusk with a cacophony of squeaks and caws amid hundreds of flapping wings. The desert nights had us tightly bundled up. Jackets would be shed the following morning as we trudged a few yards up the hill to excavate the Hellenistic temple at Sehyak in the blazing autumn desert heat.

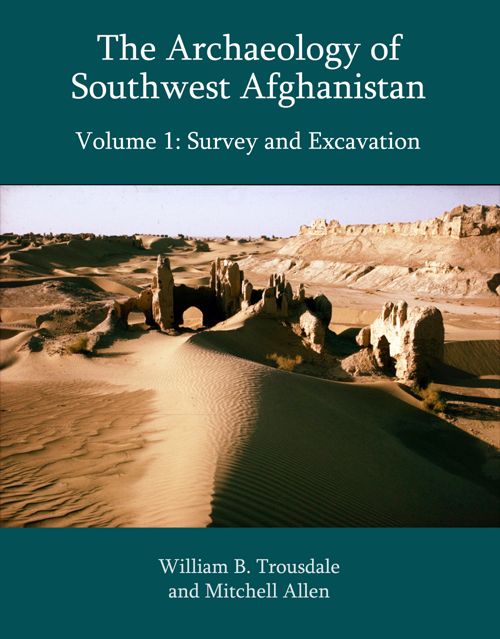

“It needs to be a large single volume so people can have all our findings in one place. I hope the publisher doesn’t limit the number of photos we can use because those will be crucial.”

Bill—William B. Trousdale, then a curator of anthropology at the Smithsonian Institution—a spry, 40-something seasoned field archaeologist, was describing the report of the Helmand Sistan Project, our 10 year archaeological survey of Sistan, the 40,000 square mile southwest corner of Afghanistan, that lasted through the 1970s. I was only 23 and signed on to this project to get some field experience for my grad program at University of Michigan. Little did either of us know that I was half a year away from dropping out of graduate school and starting a career in scholarly publishing that encompassed the next 40 years. I now know much more about what publishers would and wouldn’t do than I did that evening in Sehyak. I have been responsible for publishing over 1500 books since then and writing and editing several of my own.

Before finalizing the volume for publication, Bill hoped against hope that the warfare in Afghanistan-- first the Soviets, then the Taliban, then the Americans and their allies--- would end so he could return to answer a hundred open questions about our project when he left the country in 1980. He had also been busy with a dozen other projects—writings by 19th century British soldiers in Afghanistan, a book on Asians swords and scabbard slides, one on military schools (I published that one for him), and a history of the Afghan city of Kandahar. But age had taken its toll, and Bill was clearly not going to finish our book on Sistan. When I retired from publi shing and returned to archaeology in 2016, I suggested to Bill that I help him to write up the results of our work of decades earlier.

shing and returned to archaeology in 2016, I suggested to Bill that I help him to write up the results of our work of decades earlier.

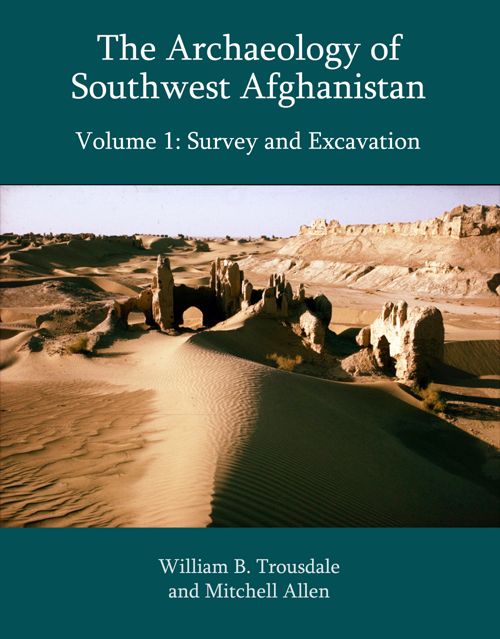

This month, in a new century, a new millennium, a new Afghan regime, and a new era of archaeology,

will see the light of day from Edinburgh University Press, written by the two of us who sat in Hajji Nafaz’s compound listening to the bats decamping for the night. Bill is 92, I’m over 70, and it has been 40 years since either of us have been to Afghanistan.

will see the light of day from Edinburgh University Press, written by the two of us who sat in Hajji Nafaz’s compound listening to the bats decamping for the night. Bill is 92, I’m over 70, and it has been 40 years since either of us have been to Afghanistan.

I took what Bill had already begun and began the belabored process of transforming 50 year old field scribblings, done in the days before laptop computers or GIS, into the comprehensive volume Bill had envisioned. The first step was to use my rusty archaeological skills to excavate his Pasadena garage where the 40 field notebooks, 15,000 photographs, 3,000 slides, and hundreds of maps hid in boxes shipped to California after his retirement from the Smithsonian.

Bill’s garage was the most extensive archaeological excavation I have ever done, and possibly the most productive. The project of assembling a small team to scan 30,000 pages of research materials for future use by scholars was equally rewarding.

Most of the ancient artifacts we found in our decade of fieldwork were left in Afghanistan and are now presumed to be casualties of decades of warfare and looting. But in the rush to flee Kabul before the advancing Soviet armies, Bill’s colleagues shipped him a small collection of objects that he had stored at the US embassy, things to be processed on his next annual visit. That collection, now in a Smithsonian warehouse, represents the only tangible evidence of our work.

Fifty years have passed. Why would anyone want to read old material like the field report of the 1970s Helmand Sistan Project? For this, I have a simple answer. There is little else. We were not the first researchers to do archaeological work in Afghan Sistan—there had been brief visits by British, French, German, and American scholars before us—but our 10 year survey was the largest, most comprehensive study of the region ever undertaken. And, given the near impossibility of doing fieldwork since then, we had the most recent material for archaeologists, historians, geographers, epigraphers, agricultural engineers, and geologists to mine for their own research projects.

Many of them have expressed interest in our findings. The Helmand River represented one of the few paths between West, Central, and South Asia and figures in many mythical and historical stories of the past. I name drop such familiar names as Zoroaster, Alexander of Macedon, Rustam, Ghenghis Khan, and Tamerlane in talking about the project. It was the home of several lesser-known medieval Islamic empires that stretched from Arabia to India: the Saffarids, the Ghaznavids, the Shansabanis. The 200 archaeological sites we recorded during our surveys and excavations represents the largest body of physical evidence of this 5,000 year history ever collected. It both clarifies and often challenges the historical narrative of those peoples and eras, previously based largely on historical writings. Bill needn’t have worried about the limits on photographs, the volume contains 1,300 of them.

As the pages of the book show, we make significant contributions to the knowledge of this region. We discovered a previously unknown Early Iron Age culture in an area that was previously thought to be devoid of occupation for over 1,000 years.We’ve found likely contemporary shrines of Buddhists, Greeks, and Zoroastrians in close proximity along the Helmand. Our excavations p roduced the first significant archaeological evidence of Saffarid Dynasty, which ruled most of Central Asia from Sistan during the ninth and tenth centuries CE. We uncovered sources of travertine and copper and associated production industries that demonstrate the links between Afghan Sistan and much wider trade networks. The dry deserts of Sar-o-Tar adjacent to the Helmand Valley contain a pristine sand-dune-covered landscape of mudbrick agricultural estates almost untouched since they were abandoned in the fifteenth century. And we cumulatively spent over half a year surveying and excavating the largest city of the region, Shahr-i Gholghola, probably the ancient fortress of Taq, discovering that the roots of the massive Saffarid-Ghaznavid citadel dated to 1,000 years before the standing ruins.

roduced the first significant archaeological evidence of Saffarid Dynasty, which ruled most of Central Asia from Sistan during the ninth and tenth centuries CE. We uncovered sources of travertine and copper and associated production industries that demonstrate the links between Afghan Sistan and much wider trade networks. The dry deserts of Sar-o-Tar adjacent to the Helmand Valley contain a pristine sand-dune-covered landscape of mudbrick agricultural estates almost untouched since they were abandoned in the fifteenth century. And we cumulatively spent over half a year surveying and excavating the largest city of the region, Shahr-i Gholghola, probably the ancient fortress of Taq, discovering that the roots of the massive Saffarid-Ghaznavid citadel dated to 1,000 years before the standing ruins.

I failed Bill in one respect. The volume coming from Edinburgh UP this month represents only one of two volumes of the Sistan report. The second volume, now being completed, includes the contributions of numerous other scholars—numismatists, ceramicists, epigraphers, geologists, among others—who examine aspects of the Sistan finds that greatly enrich the results of the project but that could not be amassed as quickly. Those insights will have to wait another year. And I’ll have much more to write on the EUP blog when the time comes.

Like many field projects, the tales of the field are almost as rich as our finds. But one continues to stand out half a century later. Our primary link to the outside world was BBC World Service. We listened nightly to Sarah Ward’s Listener’s Choice. Before embarking into the field each fall, we sent Sarah a postcard and begged her to play our theme song. She accommodated us each year with the tune “I Never Promised You a Rose Garden.”

An abbreviated version of this blog appeared on the Edinburgh University Press website. The book can be ordered from Edinburgh UP. Use discount code NEW30 for a 30% discount.

(c) Scholarly Roadside Service

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life