Mitch’s Blog

Saving Her Life

Monday, April 05, 2021

Well, it’s not exactly what you think, my sister Robin did depart five years ago at far too young an age. A phone call one late afternoon. A sudden heart attack, found hours later by a friend who had brought fast food dinner for the two of them. I wish I could have found a way to save her then.

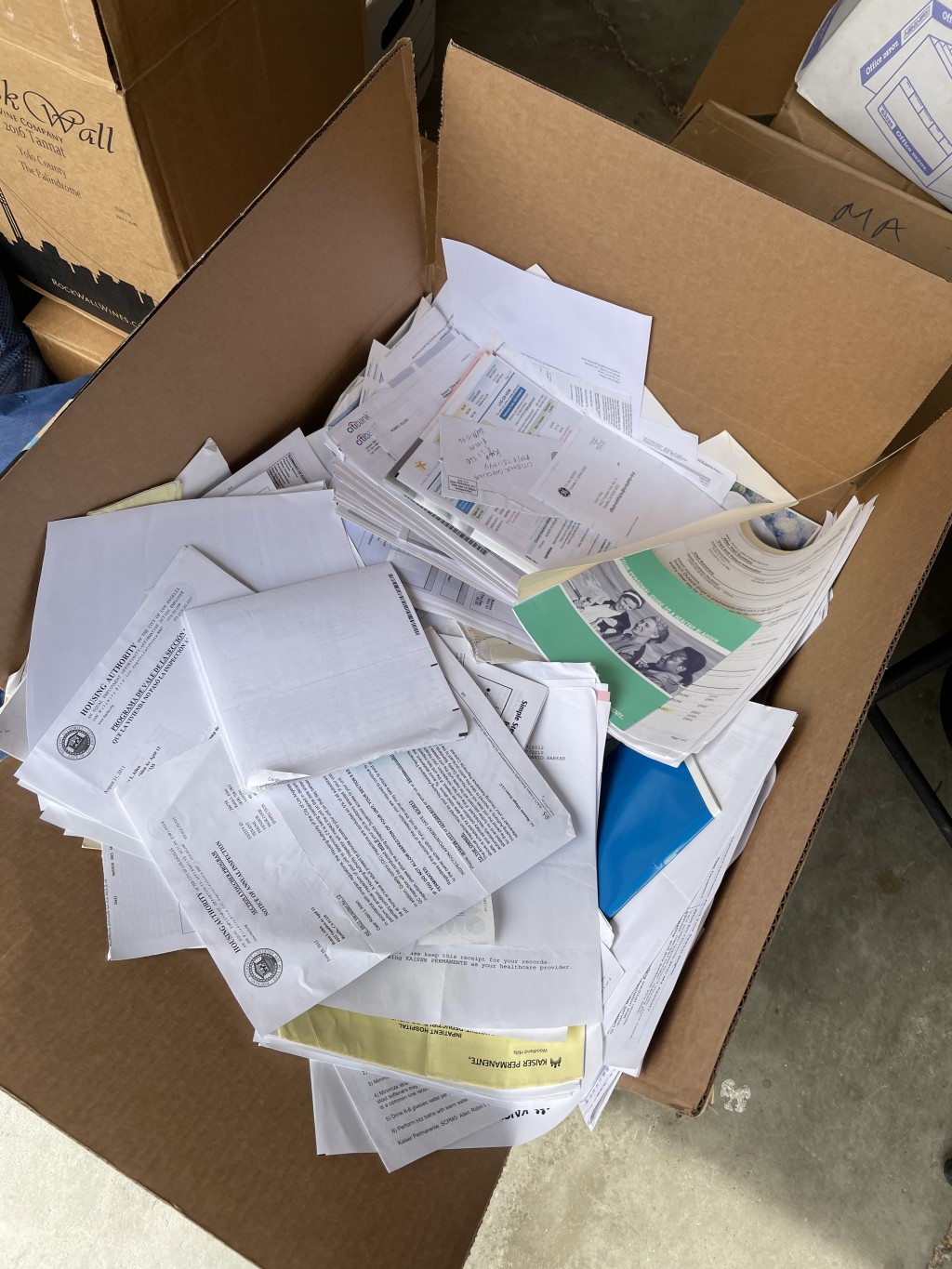

No, this is a different question, one for the long term. Will we be remembered? By whom? How will we be remembered? These questions were central all weekend as I went through boxes of Robin’s papers pulled from her apartment and stashed in our garage. I had to decide, page by page, what to keep and what to discard of the documents of my sister’s life.

It’s the right time for it. This weekend was one of celebrations—Easter, the endless Passover, my dad’s 100th birthday. I’m slamming the door on my 7th decade in a couple of months. 70. Yes, 70. In a few weeks, I’ll be father to a 40 year old daughter and a double digit-aged grandchild. Add to it the wonderfully warm weather and the stirrings of spring cleaning. Then there’s the desire that the kids’ eyes don’t roll every time they walk in the garage piled with their parents’ “stuff.” I blame Vida for most of it; she blames me. Since this is my blog, we’ll go with my analysis.

It’s the right time for it. This weekend was one of celebrations—Easter, the endless Passover, my dad’s 100th birthday. I’m slamming the door on my 7th decade in a couple of months. 70. Yes, 70. In a few weeks, I’ll be father to a 40 year old daughter and a double digit-aged grandchild. Add to it the wonderfully warm weather and the stirrings of spring cleaning. Then there’s the desire that the kids’ eyes don’t roll every time they walk in the garage piled with their parents’ “stuff.” I blame Vida for most of it; she blames me. Since this is my blog, we’ll go with my analysis.

It was time to deal with the boxes of Robin’s papers. We had already dealt with the bigger things cluttering her Reseda apartment right after her death. This was all that was left beyond some of our mother’s paintings she had kept and a small ceramic frog on the shelf of my office. Robin collected frogs.

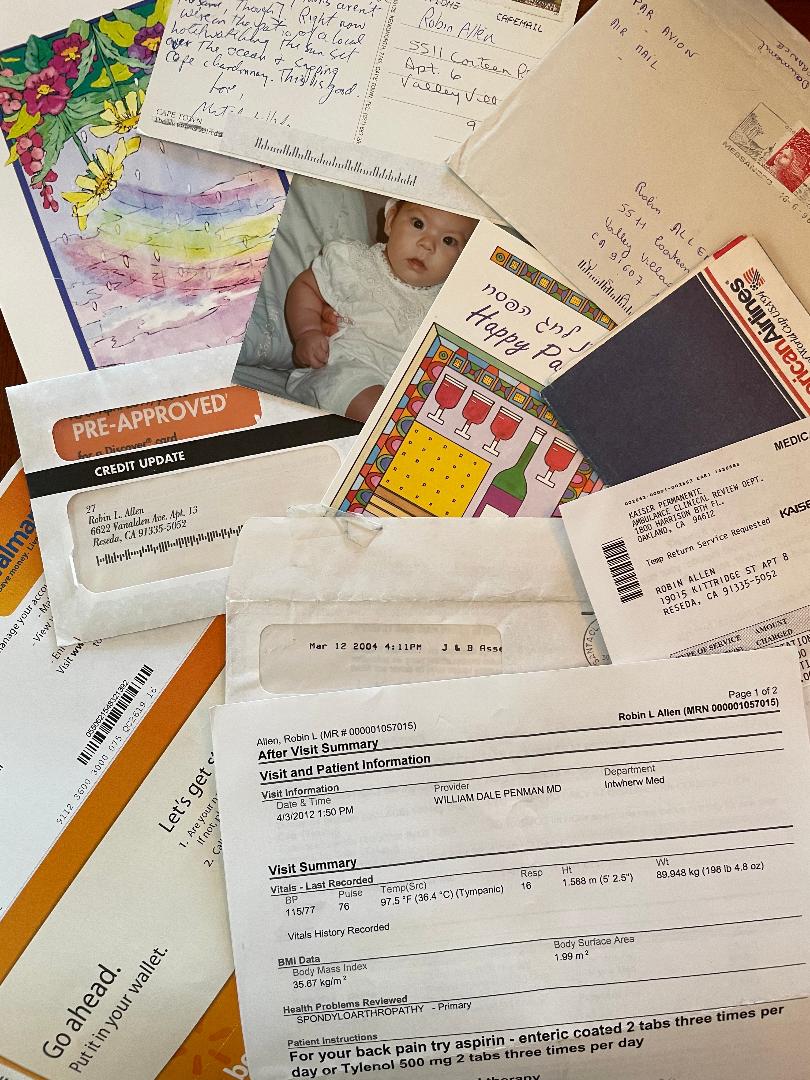

One box was fairly simple. Everyone’s daily life is a messy business and for people Robin’s age, logistics were still largely handled on paper, not digitally. Credit card bills, doctor appointment notices, social security summaries, ads for diet plans. In her last years Robin had numerous health problems, so the Kaiser envelope was bursting with visit summaries, prescription notices, and reminders of future appointments now long missed. Very little of this seemed to have lasting value for anyone who wanted to get a taste of Robin’s life.

Who would be left to remember her anyway when my generation is gone? She was never married, lived alone, and had no kids. Her closest contacts were her three siblings, their kids, and a few lifelong friends living far away. With a few notable exceptions, the nearer ones had fled, replaced by a dedicated coterie of other equally troubled adults in her various therapy groups. How much would my kids, for example, be interested in reading the details of Robin’s lifelong battle with mental illness? The groups, medications, notes from therapy sessions, and instructions from social workers. The admonishment for missed appointments. I lived many of these events with her. Would those who hardly knew her find any interest in those daily battles lasting 40 years? And how much of the grit of surviving independently while suffering mental illness is in her papers anyway?

Robin lived her life on the telephone. Untrusting of the soundness of her own judgement, she constantly triangulated with the few family members and friends to make sure she wasn’t making crazy decisions. It was a smart strategy. But for her circle, it was a daily call, or multiple daily calls until we could train her to cut it down to once or twice a week. Then the next crisis emerged and it was daily once again. Hourly. I heard much about those therapy groups, parking tickets, and missed appointments. Talked through strategies with her. Cheered her rare life successes. Tried to help her keep her life on an even keel.

The other box was much harder to sort. Diary entries and heartfelt (and very long) unsent letters. Photos, many of people I didn’t know. Letters from friends in England, France, Maryland, Santa Monica. Would my son Josh care about Jacqui’s or Nancy’s letters describing daily events in 1992? Would Elena want to revisit the postcards she sent Robin from her student year in Chile? Would Alexis care to see the many thank you notes she sent for the little gifts Robin would send her kids? Would anyone keep the cute baby photo sent by distant friends with the enthusiasm of new parents? I didn’t keep them, though I at least knew who these friends were. Would my kids read the rambling letters from Alan, living with his mother in Cincinnati, without knowing how close their fractious relationship was for the decade that Robin had her last psychotic episode. It finally imploded when she started returning to normal functioning and Alan didn’t. By now, I was in tears as I threw away things that I knew would have been important to her, but would be mere junk to someone for whom she was just the long-departed Aunt Robin.

How do you save someone’s life? And for whom?

For some reason, I found basic life documents in need of saving. Passport, driver’s license, social security card, diplomas, notary certification. That didn’t extend to her elementary school grade cards, even though I remembered many of those teachers. I had had them three years earlier.

For some reason, I found basic life documents in need of saving. Passport, driver’s license, social security card, diplomas, notary certification. That didn’t extend to her elementary school grade cards, even though I remembered many of those teachers. I had had them three years earlier.

Her bankruptcy notice. Her resume. The whos, whats, whens, wheres were kept, though I now wonder why? None of them capture her silly jokes, her love of her cat, her rambling often incoherent monologues on the phone, her equally rambling letters that showed up in my mailbox regularly. Who-what-when-where are easy. But why might be the question that has the greatest need of saving, and I’m not sure there is a way to do that in these boxes.

The sorting process was not always depressing, though I did tear up from some reminiscences, ones that she and I shared. I found Robin’s collection of 1960s Beatles fan club magazines. Who is cuter, John or Ringo? Her proof stamps of Princess Diana—Robin was an Anglophile from the year she spent as a student in Southampton.

Maybe I should file in the one folder that remains of Robin’s life the stash of letters she sent to me, now buried in a different place in the garage. Letters that spilled the issue of the day to her brother. That might be of more value to that future relative who opens the envelope labeled Robin. If so, and that descendant sighs over the complex and challenged but loving person my sister was, I will be content that I saved her life.

Handling Robin’s paper memories were not the least about Robin. Much closer to home than that. Next I’m diving into those filing cabinets filled with my papers—college notebooks, publishing correspondence, published writings, dissertation photos and notes, articles clipped out for future use, cartoons once taped to my wall. Approaching 70, that feeling of mortality has never been stronger. Nor the desire for remembrance.

What is left after I finish my sorting—things that still have meaning to me or perceived to have some future use in my remaining years-- will be the stuff of some future Allen’s task over some Easter weekend when the weather is warm and the garage overflowing with a flood of papers in need of culling.

(c) Scholarly Roadside Service

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life