Mitch’s Blog

Panning for Gold in the Filing Cabinets

Saturday, May 15, 2021

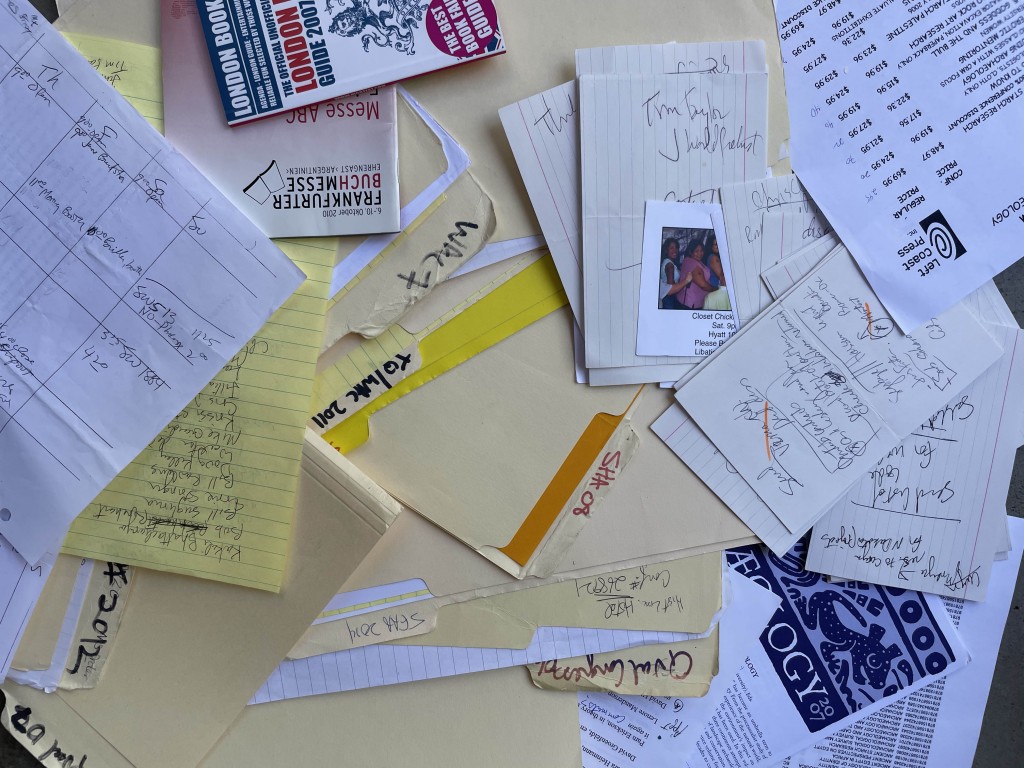

The latest pandemic task was simple: go through those five filing cabinets in the garage, jammed with papers from a 40 year publishing career and cull them down to what was important to save. A simple task, eh? I had already done this with my sister’s collection of papers and figured I had it down.

For someone who has dealt in history all his life, deciding what is “important” is both random and unclear. What makes something historical? In the archaeological work I do, little broken bits can make all the difference. A small fragment of a goblet will tell us if its past owner shopped at the neighborhood bazaar importing fancy stuff from Cyprus, Cappadocia, or China (China was exporting high quality stuff back then) or had to stick with the local knockoffs. Residue on the inside of an otherwise inconsequential jar can tell us what kind of wine people drank.

When we reached the era of written records, the clues became more abundant and no less valuable. All those obscure Dead Sea Scrolls called things like the Book of Enoch or the Rules of Community could have easily ended up in our Bible and been argued over for the past 2000 years the way we do with Ecclesiastes or Deuteronomy. References from one ancient Greek writer to the work of another whose is otherwise unknown: Would this have been the guy who made us forget all about Plato or Augustine? In the modern world, we were at risk of being overwhelmed with paper records.

What should get saved from the records of the companies I created and built, AltaMira Press and Left Coast Press? Some of it was easy. Printer bills, shipping manifests, invoices from freelance proofreaders, bank statements. Seven years saved to satisfy the IRS. The rest interest me even less than when they were sitting on my desk in the unpaid pile. Those went into the recycle bin without hesitation.

What should get saved from the records of the companies I created and built, AltaMira Press and Left Coast Press? Some of it was easy. Printer bills, shipping manifests, invoices from freelance proofreaders, bank statements. Seven years saved to satisfy the IRS. The rest interest me even less than when they were sitting on my desk in the unpaid pile. Those went into the recycle bin without hesitation.

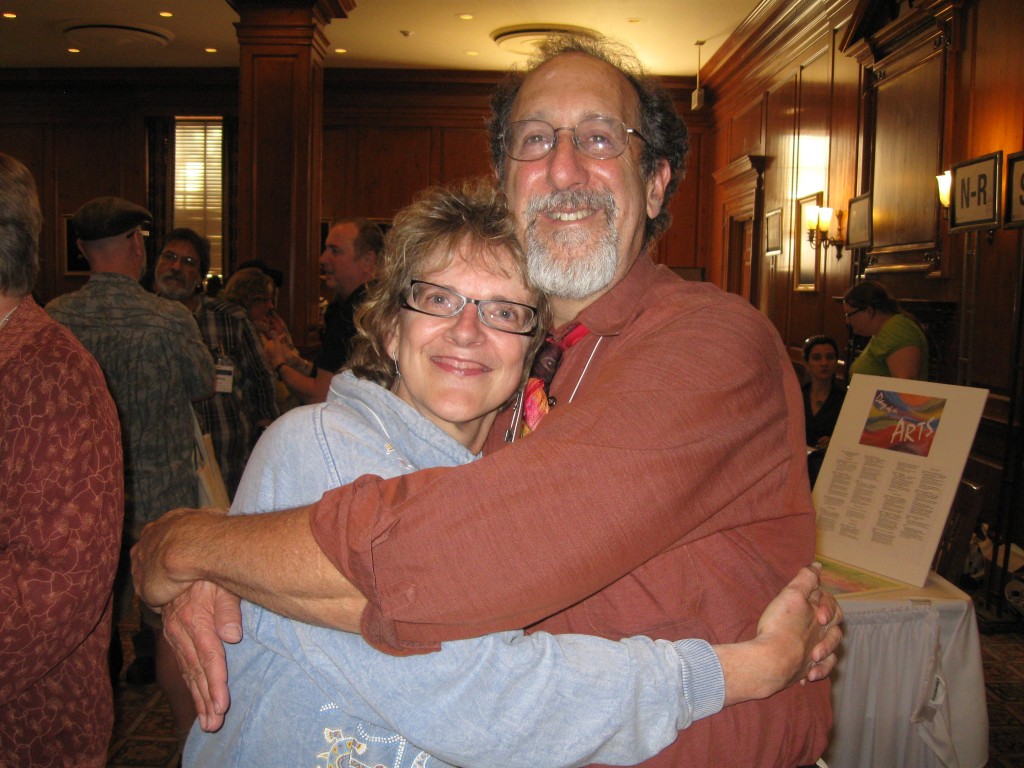

But there might be other stuff worth saving. Not so much what we did—after all, the only corporate histories written are about the victors, the ones involving people like Carnegie, Jobs, or Gates-- but interactions with those really smart scholars we worked with. The three hour dinner with Yvonna Lincoln, when she explained her latest thinking on constructivism, after we talked through Byzantine art, higher education politics, and quilting. My notes on that should be worth something. Or the phone conversations with Ashley Montagu about racism back the 1940s when he wrote Man’s Most Dangerous Myth. Over the career, I heard a lot of creative thoughts that never made it into scholarly work.

While these musing were keeping me occupied, I was chatting with my friend Carolyn Ellis, recently retired and moving to a new home in Tampa. Carolyn is one of those very smart people. She created an entire field of research called autoethnography, which brought the scholar to the center of the research project rather than looking over the wall and purportedly objectively studying what the natives were doing. There are now whole journals and organizations devoted to this idea. In anticipation of the move, Carolyn was doing the same thing I was, and, not being a historian, was tossing whole filing cabinets into the recycle bin.

“Stop!”

My historian/archivist-self revolted at this idea. After all, someday soon a graduate student, let’s call her Sophia, will be awarded a Ph.D. for writing a biography of famed scholar Carolyn Ellis and the trajectory of her work. All the clues as to the evolution of her thinking scribbled on early drafts of manuscripts, written musings with her partner Art, correspondence with colleagues, notes from her students about recent meetings. The outline to an unwritten book scribbled on the back of a pizza receipt. How could Sophia properly do her work if Carolyn erases all the clues?

I think Carolyn ignored me. After all, the task of moving all those boxes from one part of Tampa to another overruled my concern for her posterity.

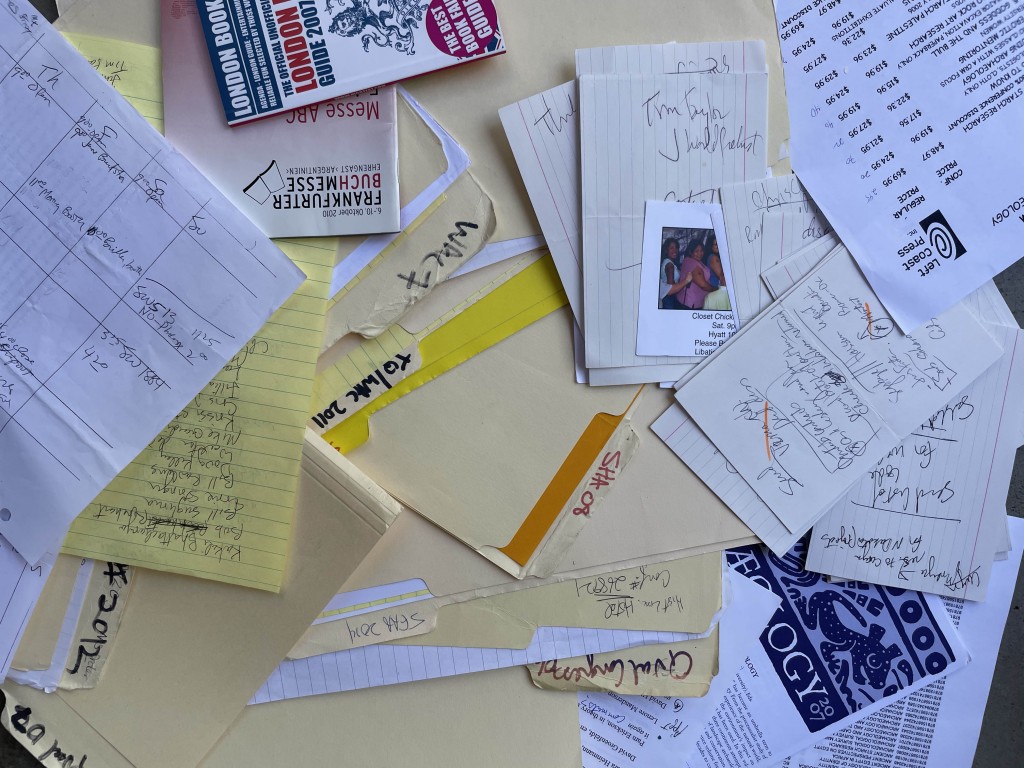

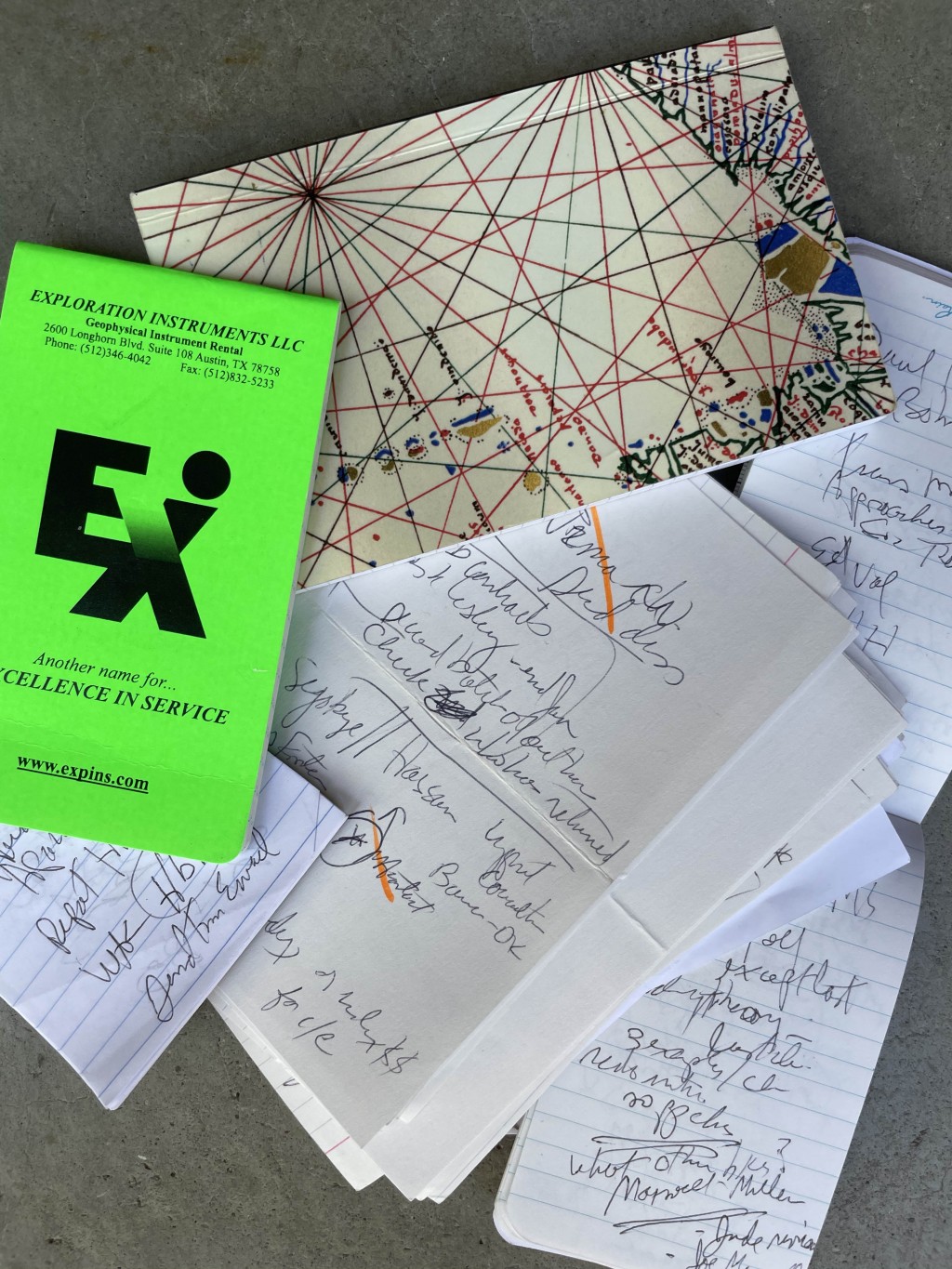

With these conversations fresh in my mind, I dove into the cabinets looking for nuggets. The first drawer was all my conference notes, likely the richest of all. I saw dozens of people at every scholarly conference and went to at least one each month for over 35 years. What gems could be found there!

Book on theory of queens. writing Am Anth article. finish identity book first.

Send list of codes for web listing

Management and Culture Wars. Anthro perspective. Comparative. 200 MSS. Write over summer.

Violence in S Af h&g. John Parkington, ask Sven O. ethnoarch paper for Lisa F. rock art and women’s stories.

Send Loubser.

Even when I could read the notes that were always kept on index cards for easy filing in the author’s book file (which I somehow never got around to doing), they were either nonsense or pedestrian. Had I really missed the important stuff, recording the deep intellectual discussions with brilliant scholars, serving as the first audience and helping them shape the thoughts they would foist upon the world? Apparently so.

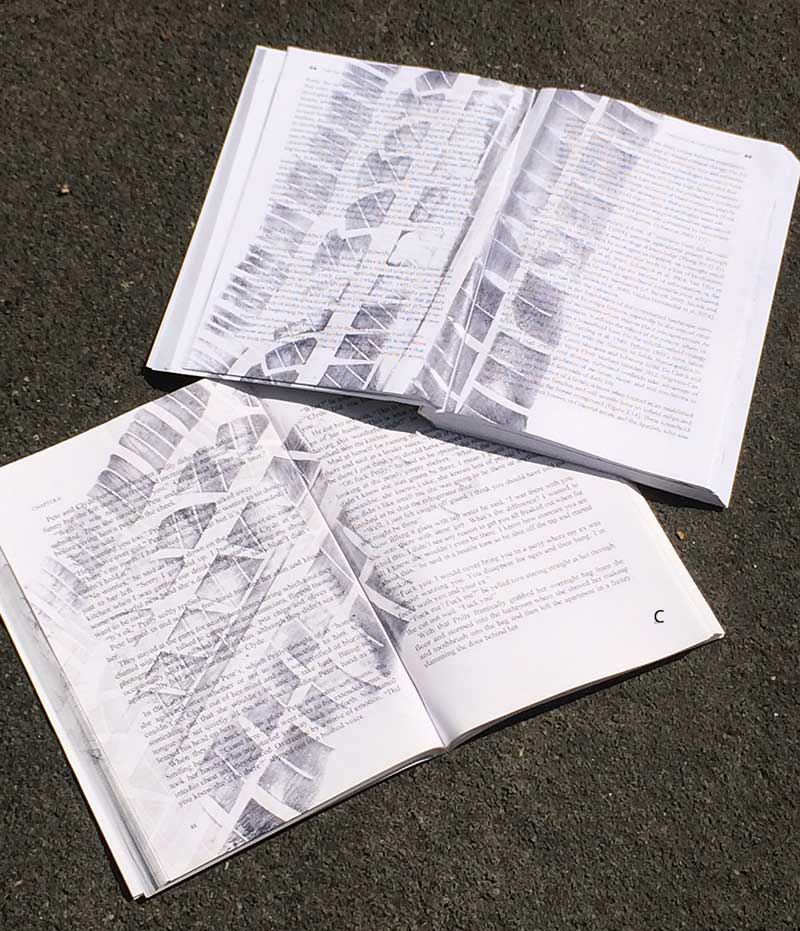

Other drawers produced mixed results. Files of notes on scholarly publishing, compiled for workshops I’ve given. Catalogs from the two presses that are already fugitive documents. The drawer with draft manuscripts sent to me, including Carolyn’s with my notes all over them, might help Sophia do her job.

After 1990, much of this intellectual exchange took place via email. I have a CD with all the correspondence from AltaMira Press on it. Good luck to the grad student in finding some way to access it to search for clues to the thinking of William Foote Whyte or Brian Fagan during that decade. But at least the CD won’t fill an entire file drawer.

So what gets saved? The letters? The catalogs? The manuscripts? The notes? Or the space in the garage? And when I’m no longer here, what will my kids do with the stuff that I couldn’t part with? Two recycle cans full of paper are already gone. If there is to be a history of Left Coast Press, I might as well stick to what is posted on Wikipedia.

I’ll have the opportunity to think this through with a bunch of guys in our monthly book group. Coincidentally, our current book is Julian Barnes, The Sense of an Ending:

“History is that certainty produced at the point where the imperfections of memory meet the inadequacies of documentation.”

I couldn’t have said it better.

© Scholarly Roadside Service

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life