Mitch’s Blog

It’s Amazing What Famous Authors Don’t Know About Publishing

Monday, January 29, 2018

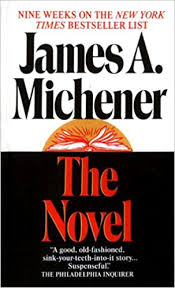

I gave up reading James Michener novels long ago, somewhere between Colorado and Alaska, or maybe it was Texas. They had turned into very bad history books compiled by his research assistants and woven into pedestrian narratives of fictional historical families over the span of centuries. I had no idea what was in his later works—Finland? Detroit? So I was surprised to find in the Cozy Corner Bookshop a Michener novel about writing and publishing called….The Novel. This one was about Michener’s own world, the experience of a novelist wending his way through a writing/publishing career. I broke my Michener ban and bought it. After authoring 50+ books, did he know anything about publishing? Could he turn his (and my) mundane professions into a page turner? Was The Novel a novel novel?

I gave up reading James Michener novels long ago, somewhere between Colorado and Alaska, or maybe it was Texas. They had turned into very bad history books compiled by his research assistants and woven into pedestrian narratives of fictional historical families over the span of centuries. I had no idea what was in his later works—Finland? Detroit? So I was surprised to find in the Cozy Corner Bookshop a Michener novel about writing and publishing called….The Novel. This one was about Michener’s own world, the experience of a novelist wending his way through a writing/publishing career. I broke my Michener ban and bought it. After authoring 50+ books, did he know anything about publishing? Could he turn his (and my) mundane professions into a page turner? Was The Novel a novel novel?

I hadn’t always detested Michener’s writing. In the days before the advent of Indiana Jones, his book The Source, about the site of Megiddo in Israel, was the trigger that got high school students first interested in archaeology. I was one of those students.** While working in the deserts of western Afghanistan, Caravans was one of the books in our small field library that I devoured. Set in the Helmand Valley, it was wild territory when I was there in 1975; it was even more unruly when he passed through two decades earlier and used it the setting of his novel about a runaway western woman.

Unlike the protagonist in The Novel, Michener was a successful author from the very beginning. His first novel, Tales of the South Pacific, won him a Pulitzer Prize and was the basis of the hit musical South Pacific. His novel Hawaii was fortuitously (or deliberately) timed to be released the year Hawaii became a state. It was followed by Texas, Centennial (Colorado), Iberia, Alaska, Chesapeake, Poland, and Caribbean. In honor of Texas being such a big state; Texas runs 1096 pages. Even small states didn’t produce short Michener novels.

Published in 1991, The Novel was one of his last works of fiction and blessedly far from his longest. The story is of a Pennsylvania Dutch author, Lukas Yoder, writing the last of an octet of novels set in Eastern Pennsylvania, where Michener grew up.  Yoder’s first four books were profound but sold miserably. Novels 5-7 caught on and made him a millionaire (only Michener and a few others can claim that). The story is told from the points of view of the novelist, of his editor at Kinetic Publishers on Madison Ave, of a book critic who finds Yoder’s work pedestrian, and of a local reader.

Yoder’s first four books were profound but sold miserably. Novels 5-7 caught on and made him a millionaire (only Michener and a few others can claim that). The story is told from the points of view of the novelist, of his editor at Kinetic Publishers on Madison Ave, of a book critic who finds Yoder’s work pedestrian, and of a local reader.

Michener couldn’t resist michenerizing the book. In the opening segment, he describes the world of the Amish and Mennonites who inhabit that corner of PA. Unlike some of his other works, Michener skips describing how the rivers were fashioned from Ice Age glaciers and sticks to details of contemporary rural life. Even so, there’s still a lengthy discussion on how to make scrapple and another of hexes found on barns and buildings. But, heaven be praised, there’s no a 50 page discursus about how paper was invented by the Chinese or moveable type by Gutenberg. The history of the persecuted Anabaptists invited by William Penn to be the first European settlers in the area is blessedly brief.

The words “dramatic tension” and “publishing” rarely appear in the same sentence. It’s hard to get an audience on pins and needles wondering if the book will hit its publication date or if Italian rights will be sold. The suspense in my world usually revolved around whether a book shipment would arrive in time for the conference without me being forced to crawl around in some dank hotel basement looking for the misplaced boxes. Tragedy is defined as the cost of reprinting an entire first run when the author’s name is misspelled on the cover.

Thus, dramatic plotlines are at a premium in The Novel. The biggest conflict seems to be with the publisher’s external reviewers, who believe the author has lost his touch. I’m sure Michener had a lot of complaints about this in his later books; I would have been one of the complainers. The resulting crisis was that they would sell only 250,000 copies of the book, not a million. Such a pity. As a central plot device, that doesn’t really compare with War and Peace or Oliver Twist. Could Yoder rewrite the story in proof stage and save the book? Not something that keeps you awake reading half the night. Better to turn on Netflix and binge watch the latest season of Game of Thrones.

I was surprised at how little he knew of the work of publishers. One critical moment required the CEO of a New York publisher to fly to Yoder’s little town for a consultation. Why? One book chain had promised to mail signed copies of the new book to a huge group of buyers, which not only put the press in legal jeopardy for mail fraud if they couldn’t accommodate, but the author as well. Besides being an obscure legal topic that no reader could possibly care about, it seems that Michener had never heard of indemnity clauses in book contracts that should have protected the author; his agent certainly included one in his. His hard-charging Jewish editor (her Jewishness was mentioned often) took the critic’s book proposal about the best and worst American writers and told the author to select different ones than the author had planned. Sure, NY publishers could be intrusive, but that would be beyond the boundaries of any editorial role I know of. When the publisher is on the verge of being purchased by a German media conglomerate, the authors run around threatening to cancel their contracts with the press and go elsewhere, as if their book contracts did not contain assignment clauses. How did Michener know so little about the rules of the game? And why did he choose to confirm how boring the world of publishing actually is?

He was a bit better on the role of the novelist: “The job of fiction is to bring to life real human beings in a real setting. Any novel about an abstract idea is bound to be bad—write about people not prototypes.” But he then tells his academic critic/author character: “Real publishing is for the conducting of a dialogue between equals. When you sit at your desk, visualize your audience your readers. As an intellectual, you’re obligated to communicate with the brightest minds of your generation, with thoughtful men and women in Berlin, Leningrad, the Sorbonne, and Berkeley.” But you can leave graduate students or professors at Cal State out of it? Sorry, James. Academic publishing is a bit broader than that.

He was a bit better on the role of the novelist: “The job of fiction is to bring to life real human beings in a real setting. Any novel about an abstract idea is bound to be bad—write about people not prototypes.” But he then tells his academic critic/author character: “Real publishing is for the conducting of a dialogue between equals. When you sit at your desk, visualize your audience your readers. As an intellectual, you’re obligated to communicate with the brightest minds of your generation, with thoughtful men and women in Berlin, Leningrad, the Sorbonne, and Berkeley.” But you can leave graduate students or professors at Cal State out of it? Sorry, James. Academic publishing is a bit broader than that.

Better to get your publishing advice from the recent article in Pacific Standard by Noah Berlatsky, things like: become famous doing something else first, be rich, have an inside connection with a publisher, and be lucky.

A book review of a 27 year old book is probably not worth much. But neither is reading the novel The Novel. The Michener ban has been reinstated.

(c) Scholarly Roadside Service

Amish house picture from Amishfarmhouse.com

**Little did I know that I would be forced to read every page of the voluminous excavation reports on Megiddo as a grad student a few years later. Even today, one of my consulting jobs is to help edit a history of Megiddo excavations by Eric Cline, who has co-directed the most recent excavations there.

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life