Mitch’s Blog

I Was A King Once

Friday, March 10, 2017

I was a king once. Four days a king. And I didn’t even remember it until last week.

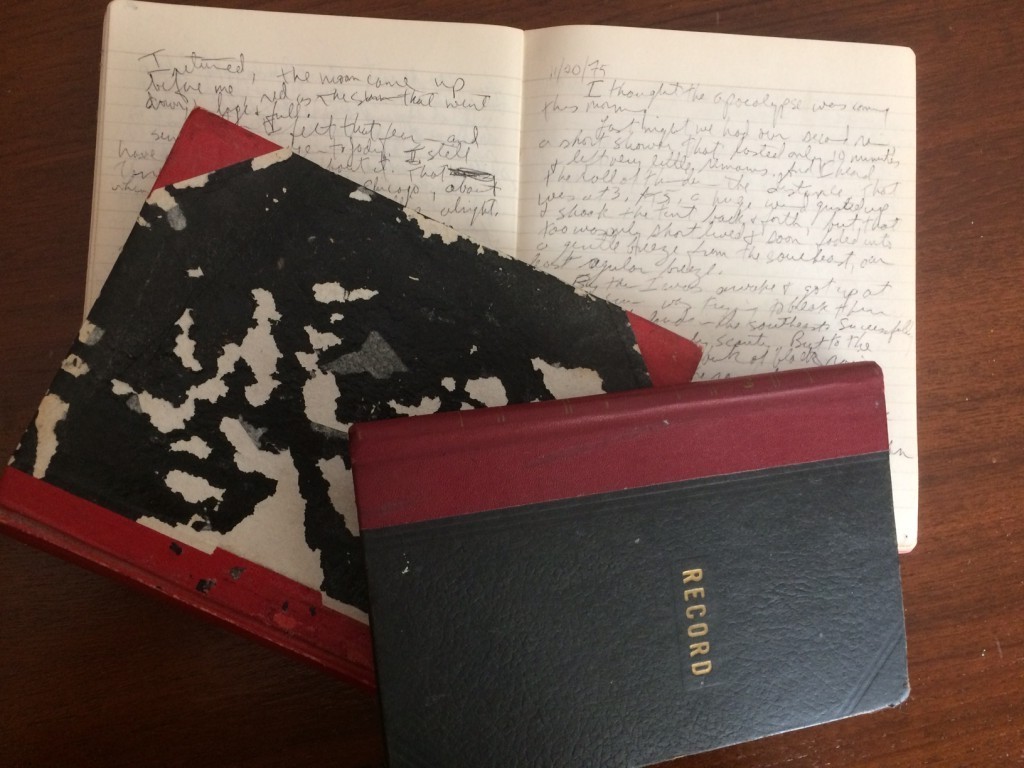

It was in the journal I kept in 1975 during my archaeological fieldwork in Afghanistan. Reading it after 42 years, I got to the entry for October 6, where I was in my fourth day of sitting in a desert

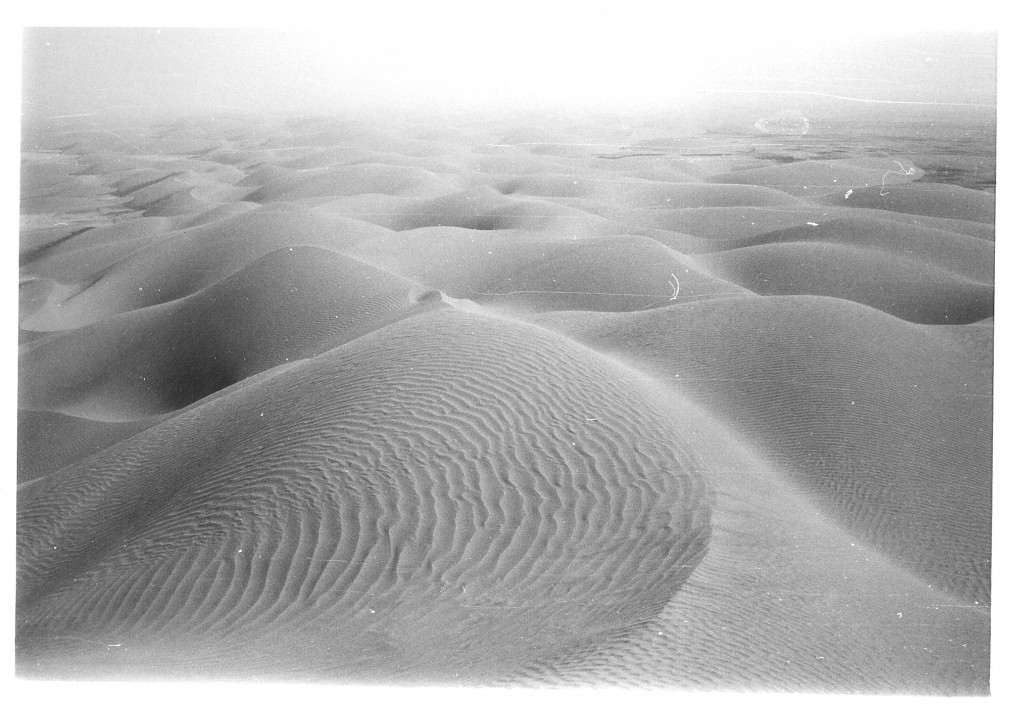

Not that this was an empty quarter. I walked along the desert pavement and found a nomad cemetery covered with piles of stone, bits of ceramic pots broken 2000 years ago, copper coins, pieces of travertine, and plastic beads. Trucks along the opium smuggling road to Pakistan could be heard two dunes to the south. A wood collector, with his young son and a donkey, wandered by once. A lizard and I stood eye to eye waiting for the other to flinch.

I don’t normally keep a journal, but wrote hundreds of pages that fall of my activities, thoughts, and emotions. Besides the exotica of the setting—three months living along the river excavating sites from cultures so remote that you don’t even hear about them in freshman world history-- it was also an emotional time, having lost my father to a sudden heart attack the previous year and having recently broken up with the girlfriend whom I thought I was going to marry.

So, here in 2017, why am I trying to read the impenetrable handwriting of a whiny, overly-dramatic and overly-impressed-with-himself twenty-something, scribbled 40 years ago? I would be worried about someone who went back to read his juvenile prose, wouldn’t you?

So, here in 2017, why am I trying to read the impenetrable handwriting of a whiny, overly-dramatic and overly-impressed-with-himself twenty-something, scribbled 40 years ago? I would be worried about someone who went back to read his juvenile prose, wouldn’t you?

Fortunately, I have a plausible answer: autoethnography made me do it. For those to whom this sounds like an app for your car or a forbidden sexual practice, autoethnography is a research tradition where the researcher is the central figure in the research project. It’s autobiography but with a research, rather than personal, goal. The term goes back a few decades in sociology, but it has only been in the last 15 years or so that it became a common scholarly practice. That should come as no surprise. Tell a self-important scholar that it is ok to write about himself, and the floodgates will open. So, in addition to autoethnography being popular, much of it is also self-indulgent and badly done. Its critics claim that all autoethnography is that. But as someone who has read more of it than most (and rejected many bad books that proclaim themselves autoethnographic), there really is something to it. It requires good introspection, good writing, and good research to be good autoethnography. Most scholars aren’t up to all three at once. But when they are, it is a far more compelling way of delivering a research story than the usual passive prose and twisted jargon that mars scholarly writing. Just read Carolyn Ellis’s Final Negotiations, my first exposure to autoethnography, and tell me that you see no value in this kind of research. She’s now working on a holocaust narrative, co-constructed with a Warsaw Ghetto survivor.

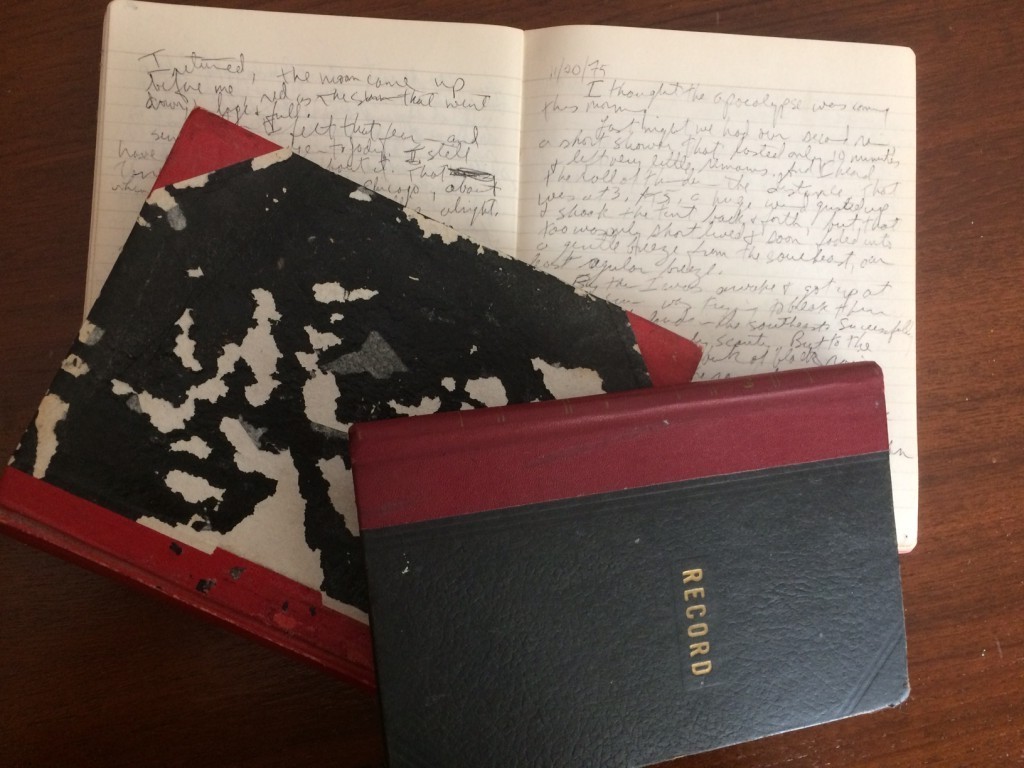

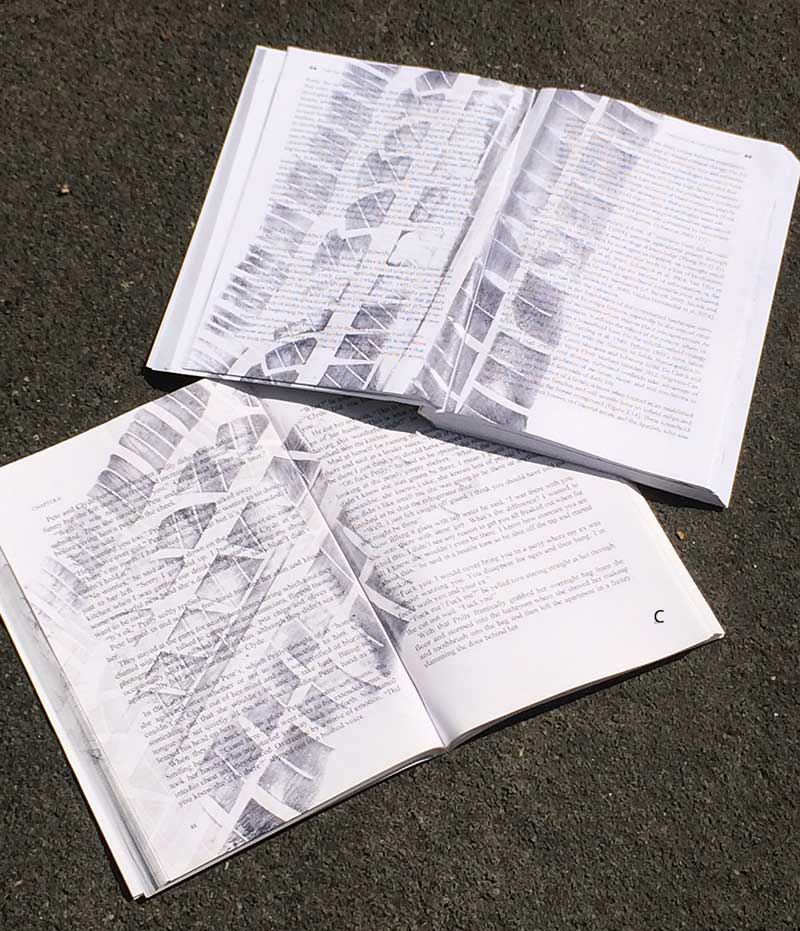

I became the world’s primary publisher of autoethnography at AltaMira and Left Coast, including key textbooks on it and a research handbook. When it came time to decide whether I was going to  Illinois this May for the International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry, one that I haven’t missed in 12 years, I thought a paper on autoethnography would be my ticket there. I was already gearing up to write up the Afghanistan excavation out of my research notebooks and vaguely knew where my personal journals were. I even had my letters home to my mother from that time. How about contrasting what someone writes as a scientist during the day against what he writes for himself at night against what he’s willing to share with his family? Analyzing different roles, different disclosures, different identities. Research, yet autobiographical. Autoethnography!

Illinois this May for the International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry, one that I haven’t missed in 12 years, I thought a paper on autoethnography would be my ticket there. I was already gearing up to write up the Afghanistan excavation out of my research notebooks and vaguely knew where my personal journals were. I even had my letters home to my mother from that time. How about contrasting what someone writes as a scientist during the day against what he writes for himself at night against what he’s willing to share with his family? Analyzing different roles, different disclosures, different identities. Research, yet autobiographical. Autoethnography!

Fortunately, the royal family of autoethnography, Carolyn Ellis and Art Bochner, are close friends and my suggestion to do an autoethnographic paper was absorbed into Art’s planned panel for the Congress. An act of friendship if ever I saw one, choosing to include an AE rookie with seasoned autoethnographers in the session. No pressure here.

What was life like in my desert kingdom? I was marooned in a saddle between high ridges covered with the endless sand dunes of the Registan. My palace had a view only to the west to the extinct volcano, Koh-i Khan Nashin, which loomed over the river valley.

It has become the landmark of our lives, changing from red in the early morning, to an undistinguishable dark color during the midday waves of heat, to a black silhouette, lifting its profile to hide the sun in the evening. From here, it looks like some prehistoric quadruped, his head with a double horn, the prickly ridge of his back ending in a smooth tail with lethal spikes at its tip… The Gabab, Great Beast of Baluchistan, turning, slumbering after its violent youth so many millennia ago.

Every king needs subjects. I had an air force of them.

Thus Mitchell Allen, ruler of the desert of Registan, purveyor over the distant Helmand River, indolent captive besieged by flies of every size and pitch. What if a Greek chorus contains just the buzzing of flies, the most natural of all sounds, the most pervasive, Afghanistan’s national bird.

My daily routine? Simply put, I was bored.

After one gets over the beauty of this spot, the few exciting and interesting discoveries, the few nice views of the desert, the couple of photos to show your friends next year, then it all becomes heat of day, cold of night, flies, and what to do until the next meal.

What made my kingdom glow were the nights.

For there is a myriad of stars and then another myriad, and still another. Bright and dim, twinkling and still, colors even... Shapes are pictured in your mind far beyond the few bears, scorpions, and warriors you half remember from school. And shooting stars, some so quick that they are a memory before a sighting, some like fireworks on July 4. So, lying in your cot buttoned up tight against the cold that is sure to come, you lie and gaze at the eternal heavens. The slouching beast and waves of sand become mere memories of a small dream against this vision of eternity. And when the cold awakens you several hours later, you peek out from your bag again and see how the configurations have changed and how the crown has turned.

Not so bad for a 24 year old archaeology student, if you ignore the “eternal heavens” and “slouching beast” cliches. And therein lies the problem. The comments above were carefully selected and wordsmithed. Left out are the crass comments about our Hazar cook Barat, the sniffling of having been the one left behind, and my worst linguistic howlers. To be good autoethnography, it needs an honesty and authenticity that I’ve carefully left out. Not an easy task, especially for a publisher more accustomed to listen to scholars yammer on about their projects and details of their lives than disclosing his own.

I still have two months to learn how to evince that candor and introspection before I present my first autoethnography. If you happen to be wandering through Champaign, IL early afternoon on May 19, stop by Congress in the Illini Union. We’ll all see how it turns out then.

Afghanistan photographs courtesy of Helmand Sistan Project

(c) Scholarly Roadside Service

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life