Mitch’s Blog

How a Copyedit Review Ruined My Day and Enriched My Life

Friday, May 22, 2020

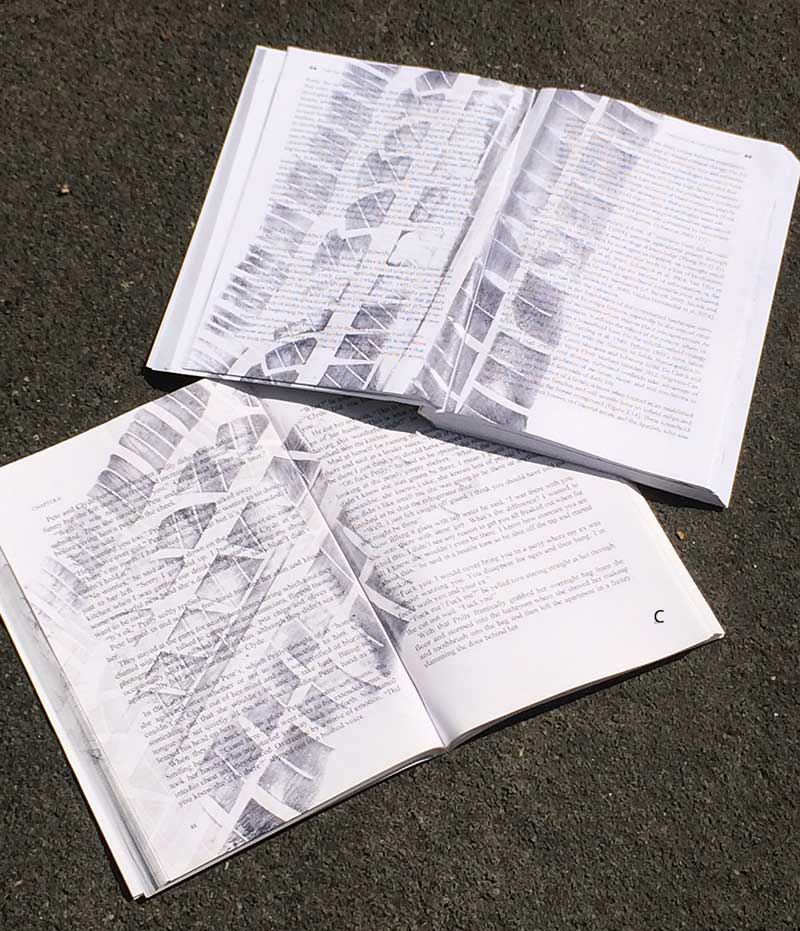

One of every author’s nightmare days. The copyedited manuscript comes back pointing out all the inconsistencies, poorly drawn phrases, missing references, and unintelligible sentences. (Why didn’t the copyeditor understand that sentence?) That day was yesterday. Rather than it being a faceless edited file coming from the publisher’s automated workflow program, I had the advantage that my copyeditor was Michael Jennings, with whom I have worked for well over a decade at Left Coast. His eye is as good as it gets and I know I can trust his edits.

Michael’s copyediting was for the book I just edited from my former Afghanistan colleague, the late Ghulam Rahman Amiri. His book, The Helmand Baluch, 40 years overdue for publication in English, will be the sole ethnographic description in the past century of the villages along the Helmand River in southwest Afghanistan, where Mr. Amiri and I worked on the Helmand Sistan Project in the 1970s. The ethnography was translated from Dari to English in the early 1980s, then sat for half a lifetime until I recently found it in Bill’s garage and spiffed it up for publication (expected from Berghahn Books later this year). Sadly, Mr. Amiri won’t be around to receive the accolades. He passed away in Denmark in 2003.

Besides it being the only modern ethnography of this region (now irrevocably changed after 40 years of warfare) and one of the few ethnographies ever written by an Afghan scholar, it contains the project director Bill Trousdale’s extensive notes on Amiri’s work. Expanding on some points that Amiri mentioned only in passing, sometimes disagreeing with Amiri’s conclusions, Bill’s commentary adds a whole new layer to the contents.

So when Amiri casually mentions the ancient towns of Lash and Juwain in chapter one, Bill adds a lengthy note, quoting the first European visitor’s description of those towns. This includes

So when Amiri casually mentions the ancient towns of Lash and Juwain in chapter one, Bill adds a lengthy note, quoting the first European visitor’s description of those towns. This includes

The cliff on which it stands has many caves cut in it, and there are said to be subterranean passages, to which perhaps the women of the garrison could retire in case of its being attempted to shell the fort; but most of these passages have neither [either?] fallen in, nor [or?] been stopped up.

Bizarre. It’s a direct quote. Did the author use either/or or neither/nor? He cites p. 332 of British Lt. Edward Conolly’s 1841 work for this description. But Bill never got around to completing references while he was annotating the book in his minute scrawl back in the 1980s. A direct quote should be exact and needs a reference. That job got left to me.

Fortunately, this was an easy one. Lt. Arthur Conolly was a well known figure to those who study the British in 19th century India and  Central Asia. He was author of one of the best known traveler accounts of his day, the 1834 Journey to the North of India through Russia, Persia and Afghanistan. He invented the term The Great Game to describe the machinations between Britain and Russia over Afghanistan, and went under the name Khan Ali when in disguise spying on the Russians. One general described him as “a man of an earnest and noble nature, running over with the most benevolent enthusiasm, and ever suffering his generous impulses to shoot far in advance of his prudence and discretion.” (Kaye 169) Think of him as the Jason Bourne of British India. Certainly his travels had carried him to Lash.

Central Asia. He was author of one of the best known traveler accounts of his day, the 1834 Journey to the North of India through Russia, Persia and Afghanistan. He invented the term The Great Game to describe the machinations between Britain and Russia over Afghanistan, and went under the name Khan Ali when in disguise spying on the Russians. One general described him as “a man of an earnest and noble nature, running over with the most benevolent enthusiasm, and ever suffering his generous impulses to shoot far in advance of his prudence and discretion.” (Kaye 169) Think of him as the Jason Bourne of British India. Certainly his travels had carried him to Lash.

I dropped that into the reference section of the book while I was prepping things for publication. Michael, as any good copyeditor should, pointed out a couple of discrepancies: Edward or Arnold Conolly? 1834 or 1841?

And thus began a morning’s journey through the murder and mayhem of 19th century British India.

Surely Bill must have meant Arnold. Fortunately, Conolly’s book was easy to find. Many of those old out-of-print books have been scanned and put online over the past decade by Google, the Hathi Trust, the Internet Archive and others. But p. 332 of Journey had a description of how the Sunnis hated the Shia and vice versa, not a description of Lash. Something was wrong.

It turns out Arthur had a brother Edward. He was dispatched by the British military to Sistan in 1839 with a surveyor, Sergeant Cameron, to map out the area for future needs. Not very subtle, the British invaded Afghanistan later the same year. Edward wrote a detailed “Sketch of the Physical Geography of Seistan” accompanied by a detailed map, published in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. But a trip to this almost 200 year old journal issue also proved fruitless. Edward speaks at length about the path of the river, salination of the soil, the boar, camels, and deer in the bulrushes, and most emphatically about the flies, “their numbers were incredible, the horses were nearly maddened” and the humans endlessly bitten. But not a word about Lash or Juwain.

Back for more web searching through the Bengali journal. “Notice of Amulets in use by the Trans-Himalyan Boodhists,” “A short Memoir of Mechithar Ghosh, Armenian Legislator,” “Vocabulary of the Ho Language.” The South Asian Scientific American of the mid 19th century. After numerous blind alleys, I ran across “Journal Kept while Traveling in Seistan. By the late Capt. Edward Conolly,” from 1841 and sure enough, on p. 332 as promised, was the quote I was looking for. (It was neither/nor, not either/or). A several hours work for just a couple of n’s. I had a rare experience of being thankful to Google for having made this all possible from my desktop, rather than having to fly to Kolkata to look up the journal issue.

Back for more web searching through the Bengali journal. “Notice of Amulets in use by the Trans-Himalyan Boodhists,” “A short Memoir of Mechithar Ghosh, Armenian Legislator,” “Vocabulary of the Ho Language.” The South Asian Scientific American of the mid 19th century. After numerous blind alleys, I ran across “Journal Kept while Traveling in Seistan. By the late Capt. Edward Conolly,” from 1841 and sure enough, on p. 332 as promised, was the quote I was looking for. (It was neither/nor, not either/or). A several hours work for just a couple of n’s. I had a rare experience of being thankful to Google for having made this all possible from my desktop, rather than having to fly to Kolkata to look up the journal issue.

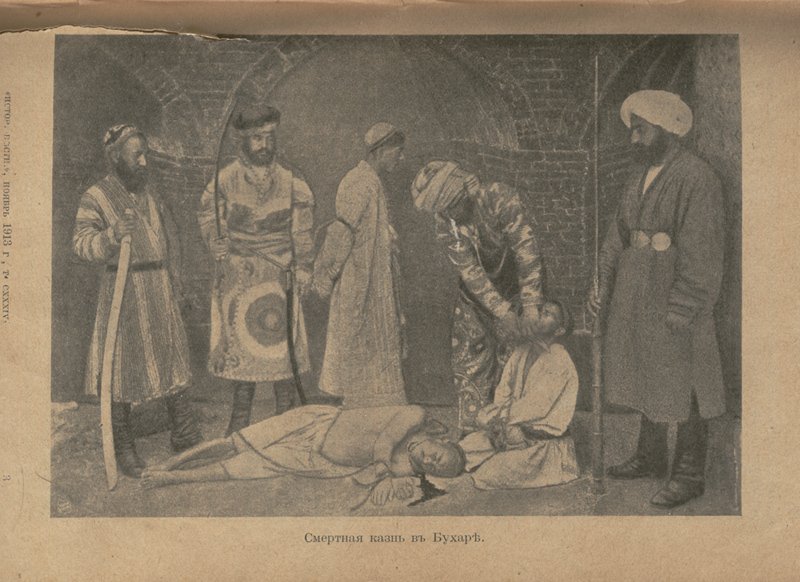

Things did not turn out well for the illustrious Conolly family. In 1840 Arthur was sent on an unofficial mission north to scope out what the Russians were doing. He was captured, imprisoned, tortured, and executed by Nasrullah Khan, Emir of Bukhara, in 1842. Edward didn’t fare any better.  During the British march to capture Kabul in 1840, they routed the local Afghan militia at Tootundurrah almost without casualties. Almost. Edward had just joined the march as aide-de-camp to General Sale that very day and took a bullet through his heart, “killed by a dubious hand at a petty fortress in Kohistan.” [Kaye p 557] Conolly brother John, died of a fever as a prisoner of the Afghans in Kabul in 1842. [Sale 392] The fourth, Henry, was murdered by fanatics in Malabar a decade later. Even Edward’s companion, Sergeant Cameron, got consumption on the return from Sistan and was ordered to evacuate to India. He was ambushed and cut down by a mob of Afghans in the Khyber Pass.

During the British march to capture Kabul in 1840, they routed the local Afghan militia at Tootundurrah almost without casualties. Almost. Edward had just joined the march as aide-de-camp to General Sale that very day and took a bullet through his heart, “killed by a dubious hand at a petty fortress in Kohistan.” [Kaye p 557] Conolly brother John, died of a fever as a prisoner of the Afghans in Kabul in 1842. [Sale 392] The fourth, Henry, was murdered by fanatics in Malabar a decade later. Even Edward’s companion, Sergeant Cameron, got consumption on the return from Sistan and was ordered to evacuate to India. He was ambushed and cut down by a mob of Afghans in the Khyber Pass.

And all I wanted to know was neither nor/either or and it took half a day. I learned a lot about the unfortunate Conolly family in the process. On to the Chapter 2 of The Helmand Baluch.

A large amount of water gathers in the Helmand Basin in the flood season.

“When is flood season?” Michael writes. Uh oh….

(C) Scholarly Roadside Service

Portrait of Conolly courtesy of Wikipedia. Photo of Lash (c) Helmand Sistan Project, Photo by Robert K. Vincent Jr. Drawing of A Conolly murder from eurasia.travel website, original Fedorov My Office in Turkestan, 1913. Citations: Kaye: History of the War in Afghanistan, 1851. Sale, Journal of the Disasters in Affghanistan, 184--2, 1843

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life