Mitch’s Blog

Finding Dirham

Tuesday, November 15, 2022

dirham: a 15th century Mongol low value coin weighing about 1.5 grams

It wasn’t a single dirham we were hoping to find, but almost 400 of them, along with a few chalkois, drachms, and even some fals(es), the ironically-named coinage of 9th century Iran, made from silver, copper, and lead. And we were looking for them in the vastness of the Smithsonian in Washington.

When I began my work in 2016 documenting the archaeological finds from Sistan in southwest Afghanistan, a project that I had been a part of as a puppy in the 1970s, the first big step was trying to find what had happened to the various sources of data—both objects themselves and our documentation of our work over a decade in Afghanistan. That required its own excavation-- of my colleague Bill Trousdale’s garage, where many of them were hidden. Over the span of a year, we uncovered 10,000 photos, 4,000 slides, 40 field notebooks buried in the garage. The plans and maps were found in a hallway of the Smithsonian’s natural history museum. Some artifacts were found in the Museum Support Center (MSC) of the Smithsonian, sequestered in the warehouse across the river from the museum mall.

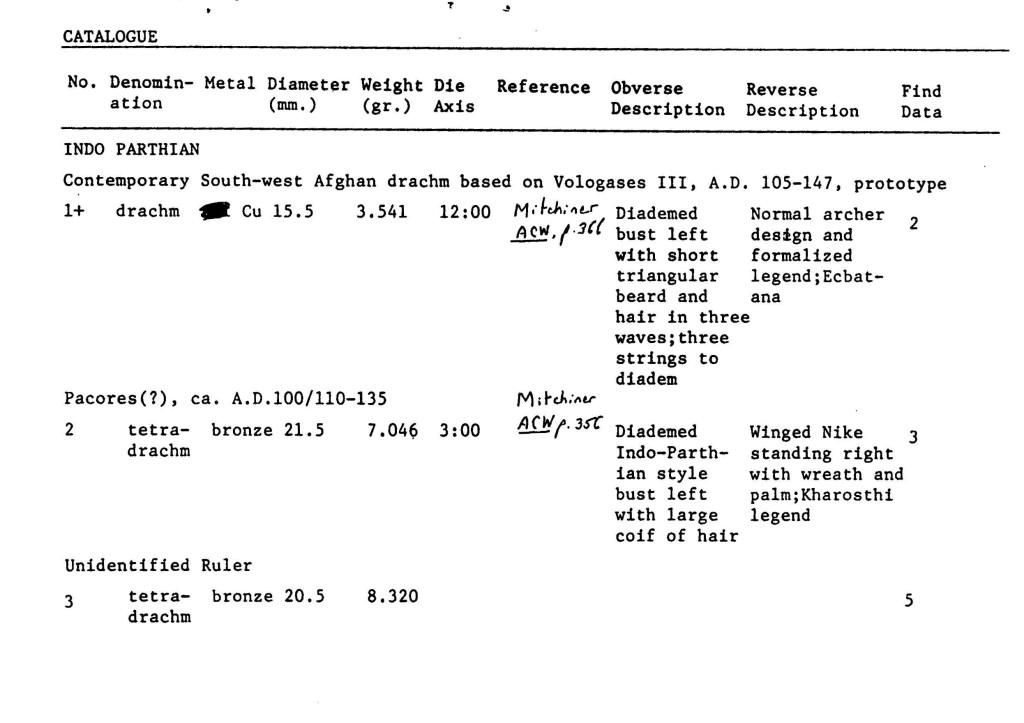

But what about the coins? Over the span of a decade of fieldwork, we had found 400 of them, dating from the 1st century to the 17th century CE. Bill gave them to Raymond Hebert, a curator at the National Numismatic Center of the National Museum of Amer ican History on the mall. Hebert’s job was documenting early American coins, but he took on the task of identifying our Central Asian coins as an under-the-table side project because of his personal interest in the topic. His bosses didn’t need to know. In 1989, he gave Bill a 30 page report on the coins—denomination, diameter, weight, inscription on them, whose mint they came from. A decade later, this would have been delivered as an Excel spreadsheet.

ican History on the mall. Hebert’s job was documenting early American coins, but he took on the task of identifying our Central Asian coins as an under-the-table side project because of his personal interest in the topic. His bosses didn’t need to know. In 1989, he gave Bill a 30 page report on the coins—denomination, diameter, weight, inscription on them, whose mint they came from. A decade later, this would have been delivered as an Excel spreadsheet.

Hebert’s report was immensely exciting for us. We could firmly date the destruction of one of our sites, Shahr-i Gholghola, to the invasion of Genghis Khan’s army in 1222, as we found small hoards coins of that date (but no later) sequestered into the wall of the bazaar dug out in 1972.  We were able to document the sequence of the maliks of Nimruz, known to rule Sistan mostly from historical records. The coins hinted at the financial struggles of the successors of Mongol emperor Tamerlane, who ruled Sistan from Herat, as their small coins were made of cheap lead with only a thin veneer of copper covering them. Currency debasement at its finest. Half of these coins disintegrated into powder after being taken from the ground. Ray and Bill discussed the importance of his findings and prepared to write research papers based upon them. But the following year, Hebert died of a sudden heart attack. No article ever appeared and the report was buried until I excavated it from Bill’s garage three decades later.

We were able to document the sequence of the maliks of Nimruz, known to rule Sistan mostly from historical records. The coins hinted at the financial struggles of the successors of Mongol emperor Tamerlane, who ruled Sistan from Herat, as their small coins were made of cheap lead with only a thin veneer of copper covering them. Currency debasement at its finest. Half of these coins disintegrated into powder after being taken from the ground. Ray and Bill discussed the importance of his findings and prepared to write research papers based upon them. But the following year, Hebert died of a sudden heart attack. No article ever appeared and the report was buried until I excavated it from Bill’s garage three decades later.

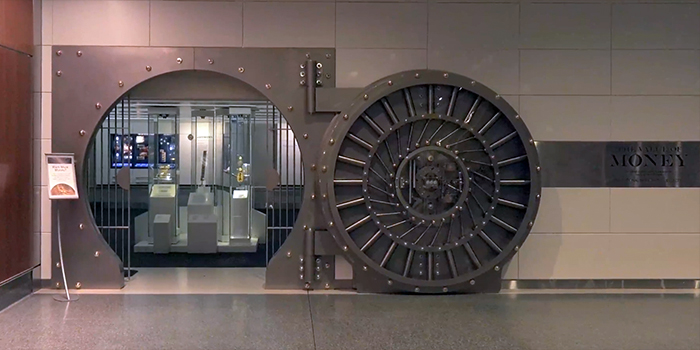

What happened to the original coins, none of which were in Bill’s garage? I wrote the numismatics curators with this story in 2017 and got a “we’ll look into it” response. Not a word since. Not surprising. Because of the informal nature of Hebert’s work, the hoard would not have been formally listed in the Smithsonian accession records. I pictured a dusty cloth bag of Afghan coins sitting in a bottom drawer of an office in the American history museum. A new curator would find the bag, have no idea of its origins or meaning, and shut the drawer again pretending he hadn’t seen them. An occasional coffee spill decorated the bag with patches of brown. I’ve never been in the numismatics office. Nor would I ever be invited to look around for the missing coins. With priceless gold and silver objects in every drawer, I’m told the department is guarded like Fort Knox. Mission Impossible.

We still had to include the coins, an important part of our survey, in our report. It was pushed back to volume 2, still in the works. At a pre-Covid conference in Naples I ran across Arturo, an Italian grad student studying Islamic coins from Afghanistan. Of course he would be interested in participating in the publication of these coins, even though all I could give him was the report and photos of some of them taken in the field 40 years ago. Arturo did wonders teasing out every bit of information that could be found in the 30 year old report, even correcting errors made by Hebert in his reading of the inscriptions based upon comparable coins found elsewhere. He presented his findings last month at a virtual conference and promised the report shortly after.

While I was in DC several weeks ago working on the rest of the collection, I mulled over placing a call to the numismatics people to raise the issue again. But that urge got squelched by the volume of work we had to do in limited days. Fortunately, Layah, a doctoral student from Irvine, joined us in the warehouse to sort out the Islamic ceramics, her specialty. In the course of drawing water jar profiles, I described the problem to her.

She had a friend, she said, another grad student. Ali was currently working in the numismatics department through a Smithsonian fellowship, studying pre-Islamic Central Asian coins in their collection. She’d ask him if he’d seen them. The Smithsonian had several other coin collections from Central Asia donated by American diplomats with a passion for coins and some extra cash. I suspected Ali had a lot of work to do.

It was only a few days later that there was a message from Ali. The Sistan coins? Sure, they were in drawers 25 and 26.  He included a photo of them, along with the long overdue Excel spreadsheet, text of a presentation Hebert gave on the coins, and some metallurgical studies that Ray had conducted on them. Why had the Smithsonian not told me they had them? The date on their accession numbers was 2017, after my original inquiry of the department. Their descriptions, now online, makes no mention of our project, just that the coins were found in Afghanistan.

He included a photo of them, along with the long overdue Excel spreadsheet, text of a presentation Hebert gave on the coins, and some metallurgical studies that Ray had conducted on them. Why had the Smithsonian not told me they had them? The date on their accession numbers was 2017, after my original inquiry of the department. Their descriptions, now online, makes no mention of our project, just that the coins were found in Afghanistan.

I didn’t ask for the return of the coffee-stained bag. But I did pass the information to Arturo, who now has to redo his paper with a ton of new information on the coins. Ali took photographs of important ones for him. And another piece of the Sistan project is ready to be completed.

Now for the next mystery: what happened to the two large oil barrels containing our artifacts left at the American motor pool in Lashkar Gah when the Soviets marched into Afghanistan in 1979? Most had not been catalogued or photographed when we left. We have no record of them, but they represent the bulk of the objects collected by our survey.

Anyone been to Lashkar Gah recently? If someone finds them, I may have to rewrite our report from scratch.

© Scholarly Roadside Service

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life