Mitch’s Blog

Entertainment or erasure

Friday, August 16, 2024

Poland had approximately 3 million Jews a century ago. Now there are less than 5,000. For those on all parts of the political spectrum who volley the term “genocide” about so carelessly, there is a lesson here on what the term actually means. My visit to Poland with Jubilee American Dance Theatre had an unexpected confrontation with my Jewish identity as well my world of dance.

I’ve never felt more identifiably Jewish than I did those weeks in a Poland without Jews. The absence was palpable, a dark undertone to the exhilaration of performing American dance and music for an appreciative local audience, young and old. Our group won the “audience favorite” prize from the festival and that was no surprise. The applause was unrestrained, except for the claps that were not there. I can’t say I heard their silence at the end of a show, I was too giddy with adrenaline, but in retrospect, the absence of a Jewish audience for a Jewish kid from the San Fernando Valley resounded loudly.

Though not the main perpetrators of this genocide, Poles have developed a schizophrenic attitude about the Holocaust. In some places they’ve turned their lost Jewish population into a tourist attraction. In others, they’ve suppressed it completely. That dichotomy was very evident in how Jewish culture was treated in Krakow versus the small towns in the Beskidy mountains in which we performed.

Most city tours of Krakow don’t happen by bus, on foot, via Segway or horse drawn carriage, though all are available. The vehicles of choice are little golf carts seating five and a driver, aggressively offered to tourists on every street corner in the Old Town. The route? The main city square and environs, of course, but there was also the option of visiting the industrial district, including the Schindler factory made famous by Steven Spielberg, and Kazimierz, the Jewish Quarter. We opted for all 3.

Cobblestone streets, 400 year old courtyard mansions, lofty churches, and suggestions for places to get the best Polish beer were among the features of the city tour, as narrated by our guide Simon. But so were the Jews of Krakow.

Szeroka Street contained several of these synagogues, a community center, and numerous restaurants offering Old World Jewish food mixed with contemporary Israeli cuisine.

Our sobering walk through the Jewish Quarter ended with lunch at one of the Jewish-themed restaurants in the square. Latkes for lunch, what else?

The infrastructure for a Jewish community was intact. Synagogues, cemeteries, shops, bookstores, houses, restaurants. Jewish murals mimicking Chagall were painted on the walls; signs in Hebrew hung over some of the stores. All it lacked were the people. So who was audience for this visible show of Jewish life? Krakow tourist websites provided the answer.

Top 10 things to do in Krakow

- Visit the historic Old City

- Tour the monumental Wawel Castle

- Descend into the Wieliczka salt mines

- Stroll through beautiful medieval churches

- Attend a concert at the Chopin Concert Hall

But also

- Tour the ancient synagogues

- Walk through the factory run by Oskar Schindler, who saved a handful of Poland’s Jews

- See remaining fragments of the Jewish ghetto wall

- Dine at a Jewish restaurant as if it were 1931

And of course, as I wrote about in my last post

- Take a day trip to see the death camps at nearby Auschwitz and Birkenau

These lost Jewish communities still exist. I found that out when I went to visit David in Jerusalem once. It was shabbat. “Let’s go synagogue hopping” he suggested. And so we did. Popped into hidden spots throughout the city that night, Hungarian, Polish, Romanian, Moroccan, each practicing its own brand of Judaism. One was a large congregation of Hassids, still wearing black coats and fur lined hats, payos curling around their ears, joyfully dancing with voices soaring to greet the Sabbath. We danced and sang with them. Gone from Poland but still to be found in Israel. In Brooklyn. In Fairfax.

Attuned now to the Jewish void, I watched for it as we went to perform at the Beskidy dance festival in the southwest Poland. The response here was just the opposite.

Jews? What Jews?

The day before, our group’s guide, Kasia, took us on the tour of her native Bielsko-Biala, the town in which we stayed. The city was once be broken into thirds, Kasia said: Polish, Jewish, German. The Jews were exterminated in 1941, the Germans exiled in 1945 when the Soviets came to town. Now the town is all Polish. Kasia’s house used to be a 3-story tenement that housed workers for the distillery next door. Both the tenement and the factory were owned by a prosperous Jewish merchant before the war. I didn’t ask when and how her family acquired the house.

The same played out in the other towns we performed in. The Jewish population there never existed.

Having produced many books about Native Americans in my career as a publisher, I recognized the parallels to the erasure of American Indian histories in the US. Native Americans lived in tipis, wore feathered headdresses, and were eradicated with the buffalo in the 19th century. Just ask any contemporary Choctaw archaeologist or Cree novelist. In rural Poland, the physical erasure was almost complete, not even preserving the Jewish equivalents of tipis and headdresses in museums.

The Jewish genocide i n Poland had moved in two very different directions: entertainment or erasure.

n Poland had moved in two very different directions: entertainment or erasure.

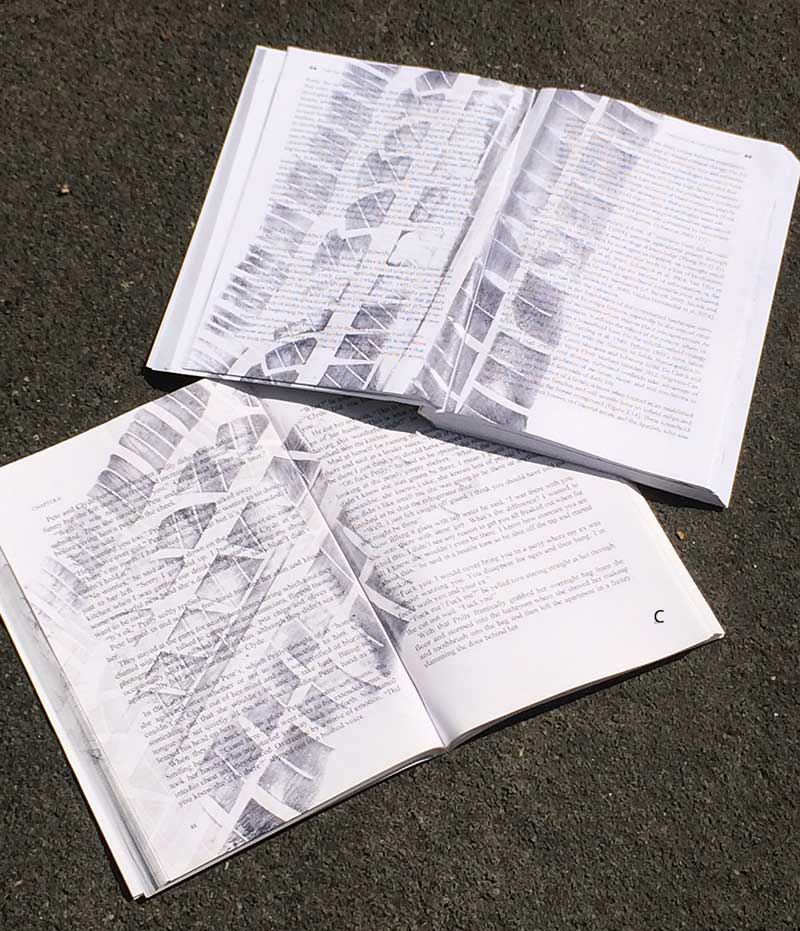

Heading back toward the hotel after our day in Kazimierz, we had one more destination planned for the day, the Muzeum Banksy. A few of his original works and lots of copies of his brilliant graffiti art made the place a wonder. But the last gallery of the museum presents pieces from Banksy’s Walled Off Hotel in Bethlehem, his stark video shot in Gaza, and murals he painted on the wall constructed to separate the West Bank from Israel. The girl with balloons, the peace dove with a target on its chest, the revolutionary throwing a Molotov cocktail of flowers were accompanied by a sound track of machine gun chatter and exploding grenades. All this only a couple of blocks from the center of Kazimierz. Truly a cosmic juxtaposition.

© Scholarly Roadside Service

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life