Mitch’s Blog

Dreaming in Tarakhun

Sunday, April 26, 2020

I had been to Tarakhun, I just didn’t remember it well. Until today.

I had been to Tarakhun, I just didn’t remember it well. Until today.

It was a late stop on our three day trip to the Afghan/Iran/Pakistani border as part of our archaeological work in Afghanistan in 1975. A memorable trip in the company of Khan Hajji Nafaz. The desert between our field camp and the border was a no fly zone unless you were accompanied by Hajji Nafaz, who had family and political contacts all through the area. He knew which unmarked dirt tracks would get us to Jali Robat and the border station. He had Mohammad Osman, his armed bodyguard, along. Equally important, he knew the road etiquette of the barren desert. Otherwise, you were likely to run into opium smugglers or bandits trying to ambush opium smugglers, equally dangerous encounters. Your jeep could get stuck in a sand dune and be 50 miles from the nearest water. None of the scenario were pretty. We were glad Hajji Nafaz was in the lead Land Rover.

We got to the spot where the three countries meet and walked in a circle around the mound of stones piled on the hilltop. It was defined as the border by the British boundary commission in the 1870s and hasn’t changed much since then. Definitely not a tourist destination. En route, we visited a couple of known archaeological sites and discovered a few others. We would pass Tarakhun on the way home.

We got to the spot where the three countries meet and walked in a circle around the mound of stones piled on the hilltop. It was defined as the border by the British boundary commission in the 1870s and hasn’t changed much since then. Definitely not a tourist destination. En route, we visited a couple of known archaeological sites and discovered a few others. We would pass Tarakhun on the way home.

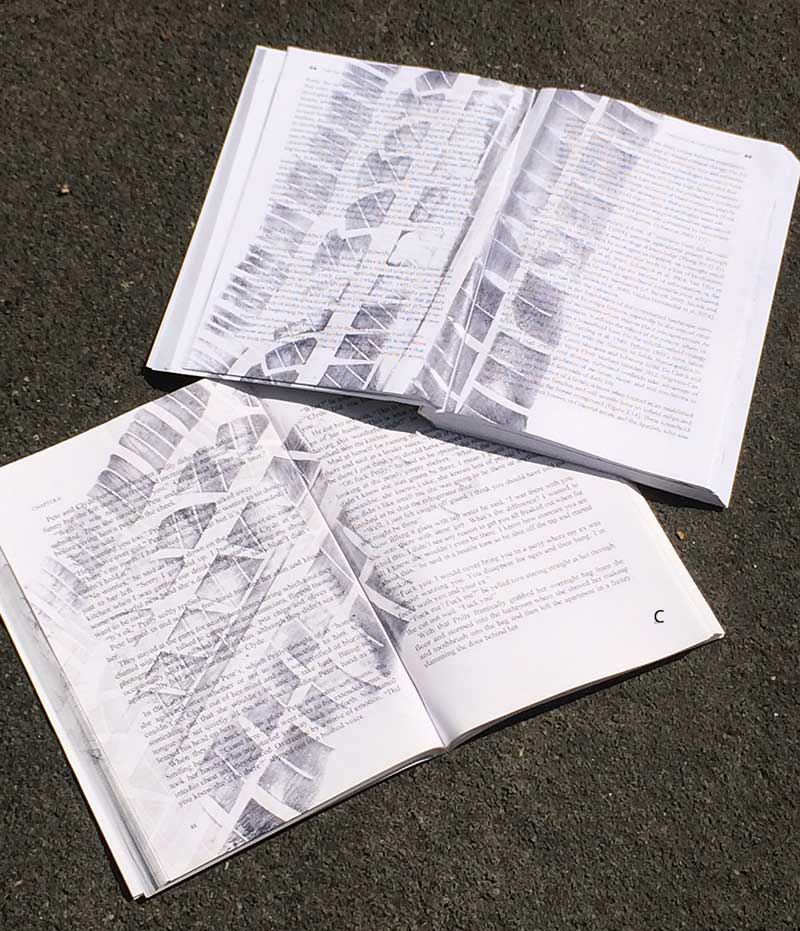

I dug through the field notebooks of our archaeological project yesterday looking for the description of Tarakhun. The site has to be included in our survey report of the region, along with 200 other ancient fortresses, towers, houses, and cities. I’ve written all the easy ones, now it was time to tackle a complex place like Tarakhun.

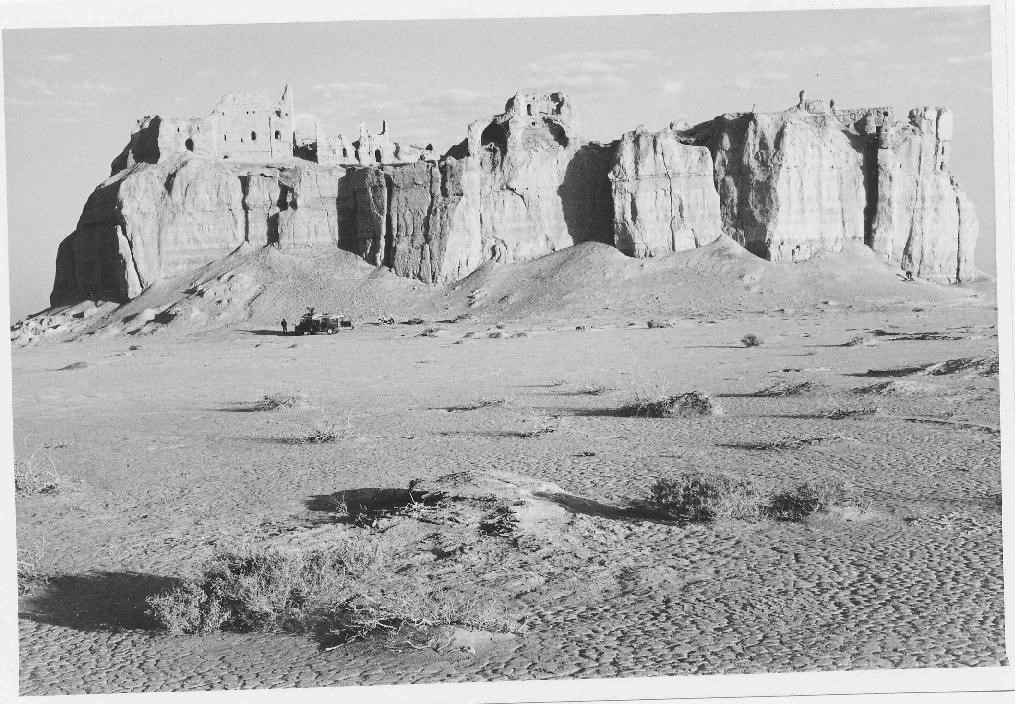

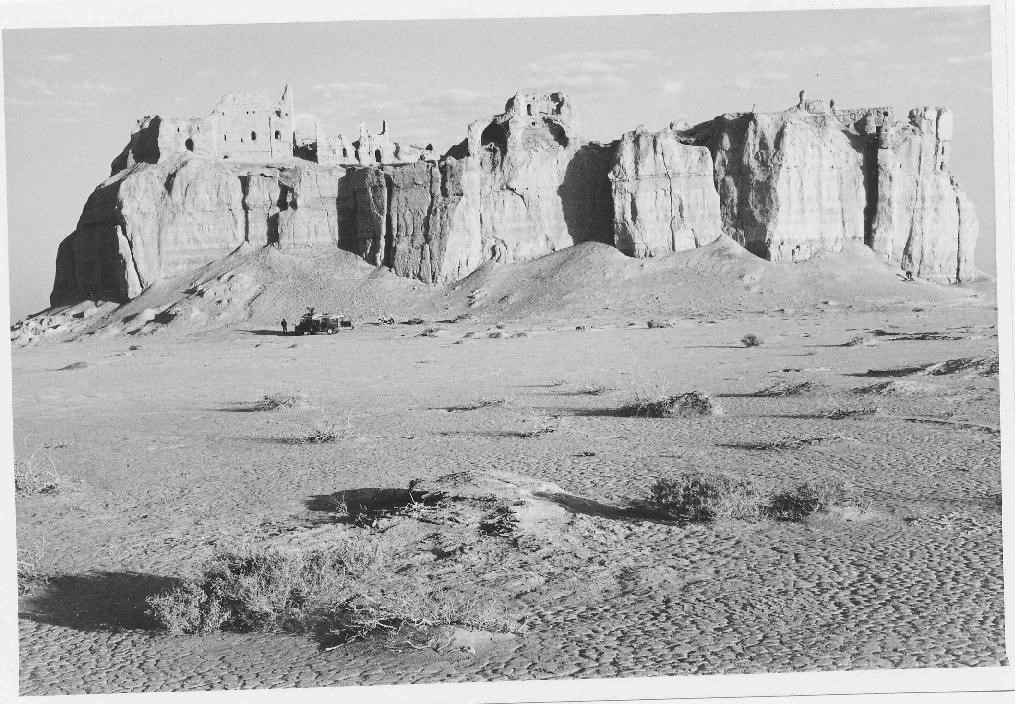

I didn’t find much. Chip had taken a handful of photos. It was even more breathtaking than I remember. Standing 100 feet above the dry bed of Rud-I Biyaban on a diamond shaped hill, its walls towered above the stark brown cliffs. Arrow slits creased the mudbrick surface of the walls. Smaller ruins dotted the high points nearby. Our team had been in the field for four seasons (two of them with me along) and had seen dozen other stunning ancient fortresses. But this one was special.

It was clearly an important place at some point in the past. My brief riffle through Bosworth’s detailed history of Sistan confirmed that. Malik Sultan Mahmud, who lived while Shakespeare was putting final touches on The Tempest and Hamlet, used it as his capital. According to contemporary sources, he lived there sumptuously with his harem while leaving his kingdom open to robbers and Uzbek raiding parties. Other accounts mention a revered fire temple on the site. Still others projected it as the home of the Persian folk hero Rustam.

While GP Tate’s 1910 report described it in some detail, my colleague Bill’s field description consisted of barely a paragraph, emphasizing that the accounts of the site dating back to the days of Zoroastrian fire temples or Rustam left no physical evidence at the place. We found nothing that could be attributed prior to Sultan Mahmud’s reign. Other archaeologists who had been past Tarakhun in the 1950s and 1960s had not added anything to Tate’s account. Could it be that the only description this key monument was over a century old and was written by a British government surveyor, not an archaeologist?

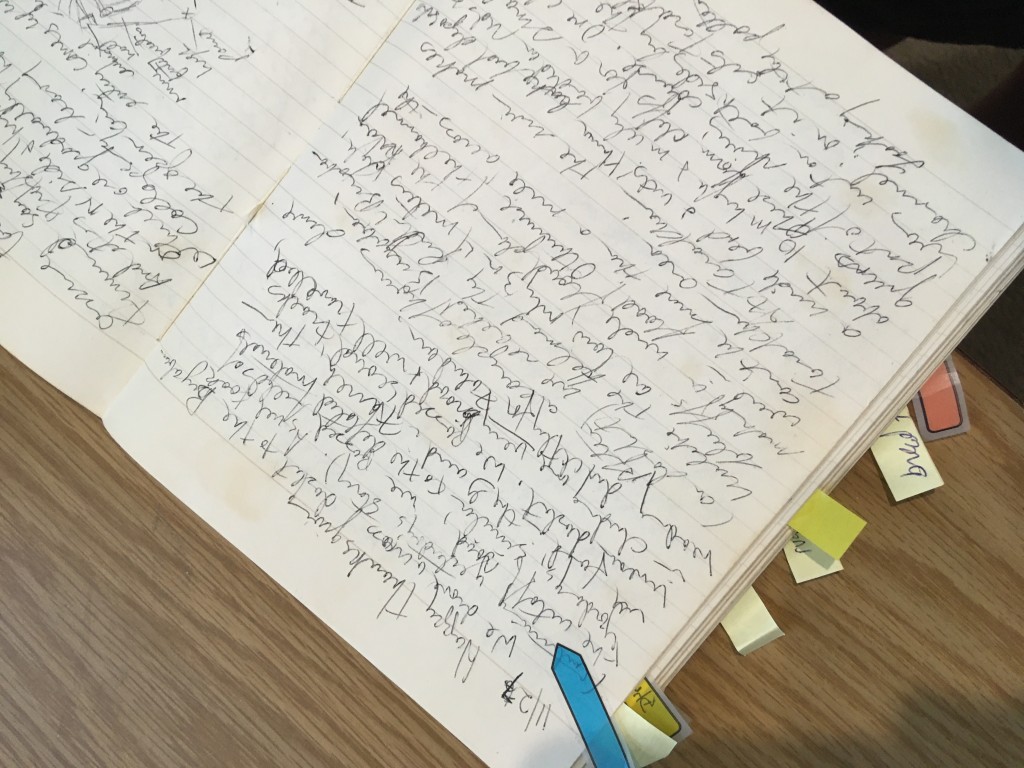

Yeah, the diary. I have only kept a daily diary a couple of times in my life, but the 1975 Afghanistan trip was one of them. It filled slow evenings when there was nothing to do but read by flickering lantern, drink Dry Sack, and listen to BBC World Service. I’ve never shown it to anyone. Most of its pages are filled with the dumb rantings of a 24 year old in perpetual crisis trying to figure out why he was placed on his planet. But occasionally my entry described what we did and saw. This unlikely source gave me a description of Tarakhun, one almost as detailed as Tate’s.

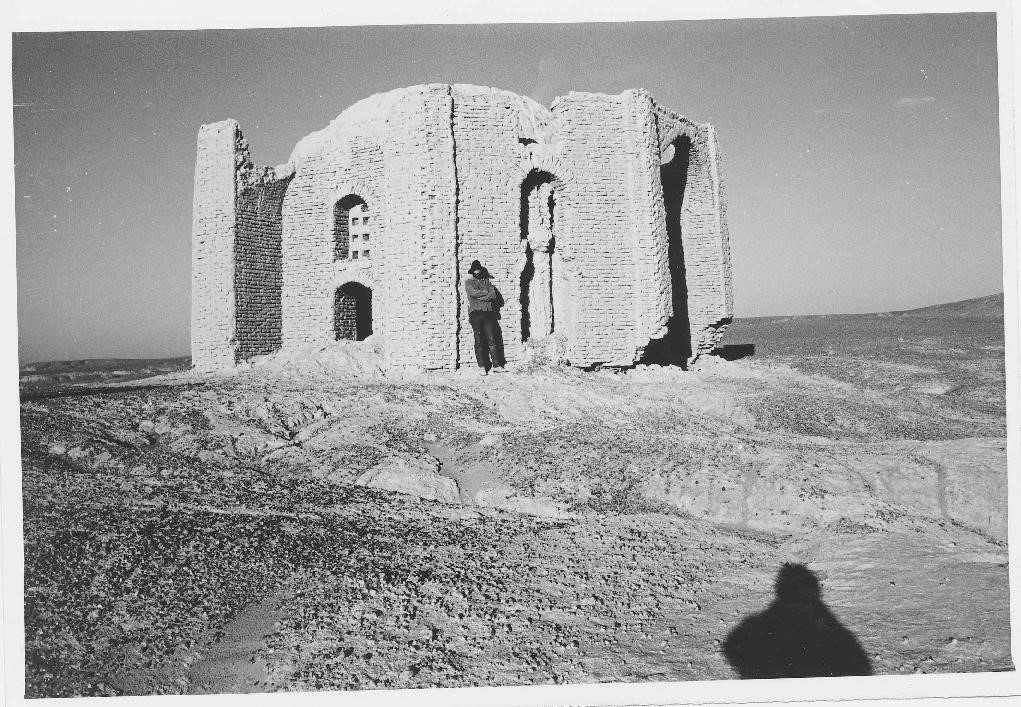

Tate hits the highlights: the towering walls, the impressive audience hall in the northwest corner, the sumptuous palace on the south side, and the brick lined well that drove through 200 feet of stone to bring water into the city. But there was more. My entry describes the interior layer of defensive walls, the decorations inside that audience hall, the octagonal mausoleum on a spur of stone outside the walls, the windmill on the cliff to the east. The mound of trash, ash, and donkey droppings that have been left in the center of the town square. The recent graffiti inside the rooms of the palace, including the carved name of one of the British surveyors. The description of ceramics that we found (and didn’t find) that provided strong evidence that no one lived there prior to the 16th century. And, best of all, a rough sketch map of the layout of the city, an important detail that none of the sources I consulted contained.

So amid my scribbles over passages in The Teachings of Don Juan, reflections on Gurdjieff’s philosophy (anyone who lived through the 70s will understand this), lamenting the loss of my father the previous year, the impending loss of a long time girlfriend who couldn’t figure out why I would rather be in Afghanistan, uncertainty whether I wanted to fight my way through the rest of my Michigan grad program (a year after penning the diary, I was out of school and into publishing), there was some Real. Live. Useful. Archaeological. Information. I’ve held onto the writings of that spoiled brat for 40 years. And it was finally worth it. My description of Tarakhun will contain information new to researchers when the report finally comes out.

So amid my scribbles over passages in The Teachings of Don Juan, reflections on Gurdjieff’s philosophy (anyone who lived through the 70s will understand this), lamenting the loss of my father the previous year, the impending loss of a long time girlfriend who couldn’t figure out why I would rather be in Afghanistan, uncertainty whether I wanted to fight my way through the rest of my Michigan grad program (a year after penning the diary, I was out of school and into publishing), there was some Real. Live. Useful. Archaeological. Information. I’ve held onto the writings of that spoiled brat for 40 years. And it was finally worth it. My description of Tarakhun will contain information new to researchers when the report finally comes out.

Then I turned the page.

Unlike Jim who always parked his sleeping bag over the next dune so he could experience the amazing nights solo, I stayed close to our small crew most of the time. I wasn’t the bravest of adventurers, even in as wild and remote a land as Sistan. Yet that night I decided to drag my cot up the hill and plant myself in the audience hall with its fallen roof and endless stars above. Tarakhun. Alone. Yes I had hesitations, I could see a whole layer of ruins underneath the fancy hall through cracks in the floor and imagined myself falling through, only to be discovered when some future archaeologist got around to excavating the place. My flashlight battery drained to zero while I was setting up. On a moonless night, I wasn’t going anywhere till dawn allowed me to skirt those treacherous holes in the floor.

The unearthly sounds of Sultan Mahmud and his harem drifted in the wind over the roar of smuggler trucks rolling over desert tracks in the far distance. I was alone and uneasy. Maybe that explains the dreams. I rarely remember mine, but those were so vivid that I hastened to write them down the next morning. I was wandering about the audience hall. Then I was an undefined somewhere else. But in each case I knew I was asleep and dreaming while I was experiencing what was happening. Waking up in the dream occurred before waking up for real. Then I would see dark clouds blocking my view of the endless star stream above the shattered roof of the hall and would bury myself more deeply in my sleeping bag.

Clearly, I had read too much Don Juan.

The morning brought the trip back to our camp near Rudbar, a sumptuous can of Swanson turkey for Thanksgiving dinner that night, and a slow forgetting of that night at Tarakhun. I relived it again only today amid the archaeological data stream and now remember the power of that visit.

I think I’ll keep the diary. Maybe even read some more of it.

© Scholarly Roadside Service. Field photographs by Robert K. Vincent, Jr. © Helmand Sistan Project.

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life