Mitch’s Blog

College Textbooks: The Next Generation

Friday, February 10, 2017

Remember those big college textbook publishers? They’re gone. Cengage. Pearson (once upon a time Prentice-Hall). McGraw and his sidekick Hill. In their place are companies that provide

What happened to their expensive textbooks, the prices of which everyone complained about? Not completely gone yet. You can still order McGraw-Hill’s Images of the Past for your archaeology students at a bit north of $200 each. The other biggies also have a few textbooks left, generally linked to some online content that the students also have to purchase, all in the 3 digit cost range.

The Big Three have been jettisoning textbooks to keep the balloon afloat for years now. Pearson sold about 300 of their social science titles to Routledge last year. Even my little Left Coast Press was able to snatch up the 7th edition of Field Methods in Archaeology, a classic work first written in the 1940s, from McGraw-Hill and half a dozen others. Unlikely players like Oxford University Press are now churning out textbooks right and left. Add to them the list of former scholarly presses like Sage, Wiley, Routledge, and Rowman & Littlefield, who have now become the textbook publishers of choice.

Before we hold our memorial services for the Big Three, are they really going away? What the hell is a “learning science” company anyway? It’s all about solving the problem that has bedeviled textbook publishers for generations now, since even greybeards like me were in college--- the used book.

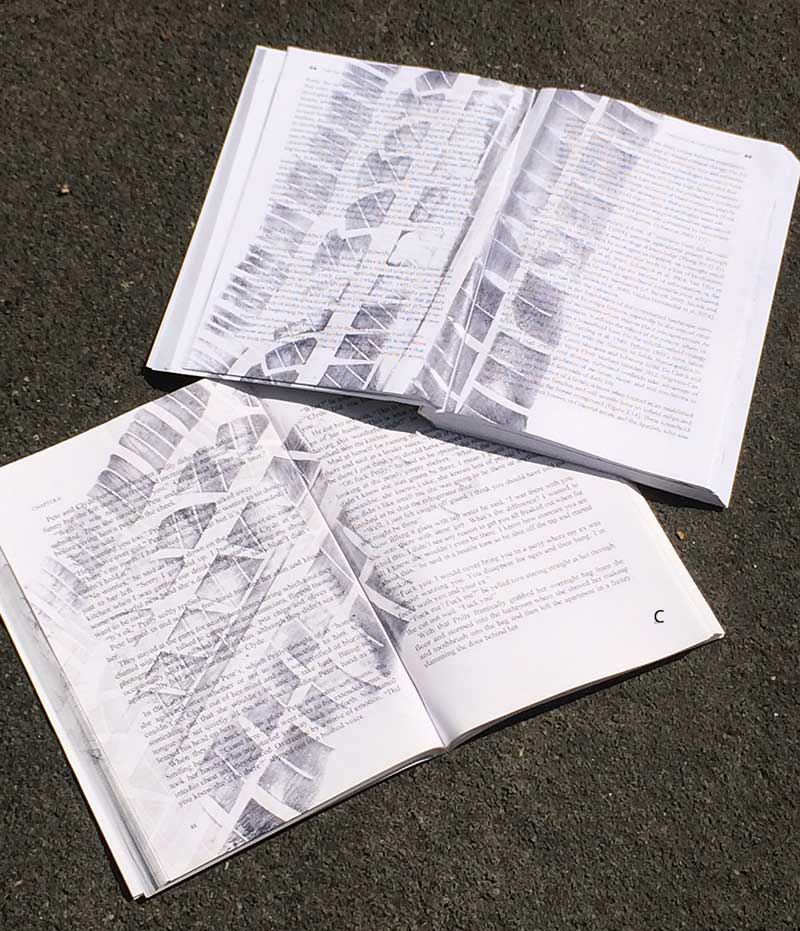

Once upon a time, the pattern was as predictable as the seasons. Each September, the students would go to the school’s bookstore to purchase those books, read (maybe) some of them during the semester, and sell them back to the bookstore when the course ended in December, pocketing the return money for their winter ski vacation or, as necessary, hoarding it for purchasing textbooks for the second semester. Spring semester: lather, rinse, repeat. The returned textbooks, now underlined in yellow and pink in many inexplicable places, would be stored by the bookstore until the next fall, when the same professor would order the same book for the same class. The students, like swallows to Capistrano, would return to their bookstore, to buy either a crisp new copy or one of the colorful used ones at a lower cost. Every few years, the textbook publisher would come out with a new edition, profs would grumble about having to update their lecture notes and reading assignments, and the supply of used books would be wiped from the bookstore’s shelves, replaced with unpinked and unpunked Second Editions. Ah, the good old days.

Once upon a time, the pattern was as predictable as the seasons. Each September, the students would go to the school’s bookstore to purchase those books, read (maybe) some of them during the semester, and sell them back to the bookstore when the course ended in December, pocketing the return money for their winter ski vacation or, as necessary, hoarding it for purchasing textbooks for the second semester. Spring semester: lather, rinse, repeat. The returned textbooks, now underlined in yellow and pink in many inexplicable places, would be stored by the bookstore until the next fall, when the same professor would order the same book for the same class. The students, like swallows to Capistrano, would return to their bookstore, to buy either a crisp new copy or one of the colorful used ones at a lower cost. Every few years, the textbook publisher would come out with a new edition, profs would grumble about having to update their lecture notes and reading assignments, and the supply of used books would be wiped from the bookstore’s shelves, replaced with unpinked and unpunked Second Editions. Ah, the good old days.

That system has gone through an endless set of shocks over the past two decades. The used book market got better organized as bookstores consolidated into a few large chains and distributors, so that books returned by students were sent to central locations and immediately reissued to different campuses rather than languishing in the bookstore basements. Other used book companies joined the party aided by the growth of electronic commerce, so that the student had many options in finding the necessary textbook from other used book vendors, Amazon, or other students. The market for new books shrank, though their production, marketing, and overhead costs remained the same. Prices skyrocketed for the purchaser of new books, since the first sale of that book had to also cover what used to be income expected from the second and third year’s buyers, who now purchased the book used, from which neither the publisher nor the author benefitted. Price increases only served to intensify the hunt for lower-cost used copies. Revision cycles on editions went from every five years to every three to alternate years in an attempt to wipe out the mass of used copies.

With the growth of electronic publications, new strategies for eliminating those pesky used books were invented and rapidly discarded. Professors were given the opportunity to create individually tailored books from large databases of articles and chapters on the assumption that no two professors would select the same set of articles and therefore no used books would be generated. Companion websites containing supplemental information, assignments, and tests were added to textbooks, requiring individualized passwords for each enrolled student, so the publisher could be assured of some sales every semester, whether or not the main textbook was sold by them or by a third party. Textbooks themselves migrated to digital platforms controlled by the publishers to minimize costs and to avoid students accessing course information from third parties. Making a bold statement, Pearson’s reps showed up to academic conferences a few years ago with a laptop and flyers, but no hardcopy books on display. Edito

Advocates for the growing open access movement urged professors to write their own textbooks for their classes and post them online for free. Knowing how badly most textbooks are written even with the editorial help of a publisher, I don’t see this as a comprehensive solution.

According to a recent report, Chicken Little was right. The sky really has fallen. The old economic models are no longer sustainable for those billion dollar companies. The new strategy, apparently started as a counter to the textbook publishers, is to offer students low cost electronic course materials through the university, giving “inclusive access” to all students in the class. It acts like the Affordable Care Act for students, if all students purchase access to the class materials, there is a much larger pool and therefore cheaper for everyone. The learning companies are moving toward adopting this model. As long as those course materials come from these publishers (and the income back to these publishers), it represents a consistent revenue flow and effectively abolishes used books. The Big Three are betting their billions on this being the answer.

But will professors, universities, and students move toward this solution quickly enough and completely enough to keep the newly-rebranded learning companies afloat? That’s up to you and your students.

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life