Mitch’s Blog

Don’t Look Now But You’re Probably Writing for a Database

Thursday, February 23, 2017

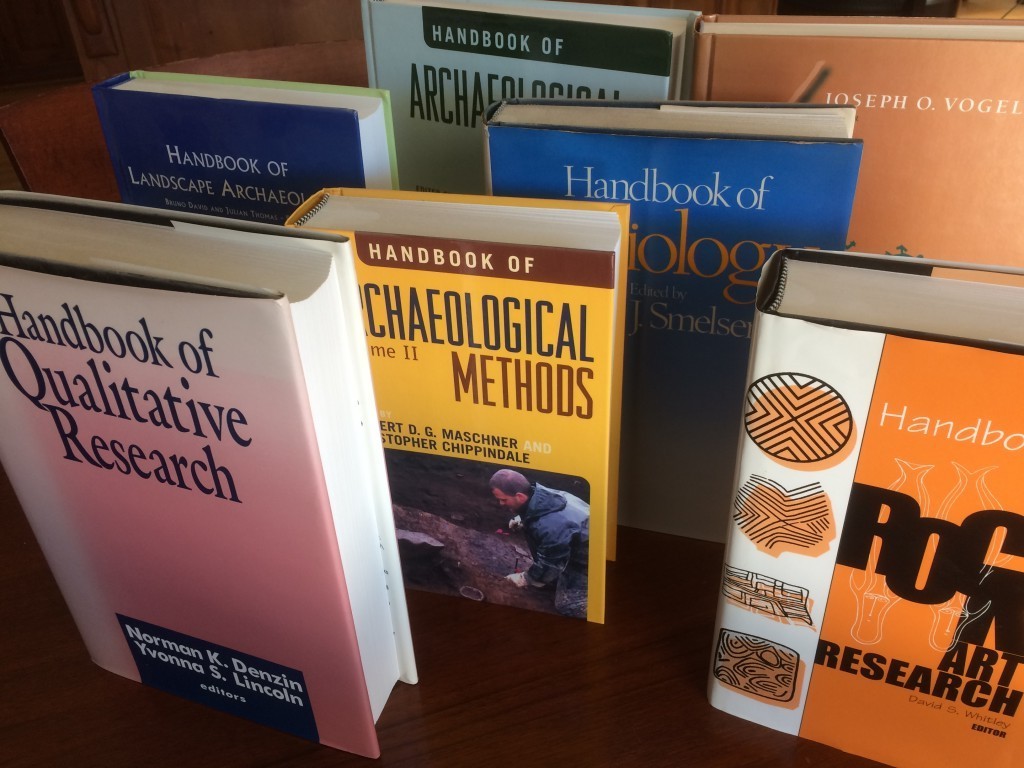

My friend Ann is probably stewing this week after having received a very mixed review of the book she coedited, the Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant.  The review spent two paragraphs congratulating the authors and editors and the subsequent seven criticizing what didn’t appear in its 58 chapters and 900 pages. I was not part of this project, but have been publisher of many other handbooks— on Sociology, Rock Art Research, Gender in Archaeology, even one on White Power, among others —and know that creating a handbook is a five year process involving endless work with dozens of authors. It’s certainly easy for things to go wrong and rare that the final product meets the original vision of the editors, let alone satisfy a picky reviewer. Ann is probably fuming over the unfairness of it all. I don’t blame her. But Oxford University Press, the publisher, probably doesn’t care.

The review spent two paragraphs congratulating the authors and editors and the subsequent seven criticizing what didn’t appear in its 58 chapters and 900 pages. I was not part of this project, but have been publisher of many other handbooks— on Sociology, Rock Art Research, Gender in Archaeology, even one on White Power, among others —and know that creating a handbook is a five year process involving endless work with dozens of authors. It’s certainly easy for things to go wrong and rare that the final product meets the original vision of the editors, let alone satisfy a picky reviewer. Ann is probably fuming over the unfairness of it all. I don’t blame her. But Oxford University Press, the publisher, probably doesn’t care.

Huh? Don’t they have much invested in this book too, both money and staff resources? Yes, but for Oxford, the function of this volume is less as a book to sell than it is part of their archaeology database. If some things are missing from one volume, it is not so consequential.

Welcome to the world of publishing databases.

Handbooks, encyclopedias, companions, dictionaries, and similar reference books have been around in the social sciences and humanities for decades now. When I presented a paper at AERA about producing them, I started with the definition: If you want to give one book to a Ph.D. candidate to memorize in order to pass their qualifying exams, this would be it. It’s the comprehensive summary of the work in a given area. They became important economic products for some publishers. The

A quick glance at Oxford’s archaeology list discloses that they have published 31 handbooks containing over 1300 articles in the past five years. They boast of having produced 24,000 articles by an equal number of scholars in 700 handbooks across 14 disciplines from classics to neuroscience. Devoting that much resources to a specific product can’t be an accident, and it isn’t. This huge outpouring was in the service of Oxford Handbooks Online, which a university library can subscribe to. Prices for a subscription are not listed on the website, but I’ll bet it’s more than your annual book budget. If you’re publishing 700 handbooks, what does it matter if one doesn’t turn out the way a reviewer would like? Publishing a handbook with too few articles on Phoenicia, too few maps, marginal architectural drawings, or a badly written piece on the Hyksos, won’t affect the library’s decision to subscribe to the handbook database.

Just so you don’t think I’m picking on poor old Oxford, you’ll notice that almost all the large scholarly presses have similar programs. While they vary as to the types of products included (books, journals, reference volumes), their size, the number of disciplines covered, it’s now a common feature on the landscape.

When Routledge purchased our modest Left Coast Press a little over a year ago, it was only a small piece of a much bigger plan to do the same thing. Our sale in 2015 came after they had already bought five other scholarly presses that year. They haven’t slowed down in 2016, adding three others that I know of since the Left Coast deal was concluded. Their Routledge Handbooks Online boasts 23,000 articles and 27 disciplines, competing well with Oxford. I’m sure that total includes Left Coast’s series of handbooks copublished with the World Archaeological Congress and our other reference books. Routledge’s website boasts that they now have 60,000 book titles and 1500 journals under their umbrella. One can make quite a few online collections with that much stuff.

Other large scholarly presses have similar programs, with many more to come. Some combine their other books and journals as well. Some divide by discipline, others are more comprehensive. But this is what publishers are pushing libraries to buy. Of course, there are problems with this system. Hypothetically, you might think Springer has a better collection of archaeology publications, but your library can’t afford both and decides to buy the Wiley’s collection instead because it more for your demanding English department, even though its archaeology listings are less relevant to your work. And that one fugitive book from a small press in Asia that is not in anyone’s collection won’t get purchased either because too much of the library’s budget is going to Wiley.

Competing with this movement toward gigantism are several commercial services that will aggregate material from smaller publishers and a couple of non-profit ones like JSTOR and Project Muse. It’s the Costco approach, even if you only eat 6 artichokes in that box of 10 you bought, it’s still cheaper than buying them one at a time.

For the scholar, this has some ramifications.

- You will continue to get those invitations to contribute an article to the Encyclopedia of Somethingorother, even when there are already three on the same topic.

- You’ll keep getting those ads to buy the Companion to Somethingnonsensical at a phenomenal discount. The publisher doesn’t expect any library to buy it at list price, so these are just supplemental sales for them. Jump on it if it’s worth your money, though first check if you can get it from your university library’s electronic collections.

- The bigger the database, the more it can sell for. They also require constant new material to justify annual subscriptions from the library. The demand for content to fatten up the database might open more outlets for your work, both articles and books. Just don’t get upset when you discover that your carefully constructed volume has been sliced and diced and offered in pieces through that publisher’s database.

- This might be particularly helpful for those trying to get their collection of conference papers published. That’s always been a tough sell to publishers, but should be easier if all they’ll do with it is stuff it into a database with a bunch of other writings on similar subjects.

Whatever the case, expect this trend toward building databases from your work to grow in the near future.

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life